A CERN for AI and the Global Governance of AI

Forward motion is a good thing

The world can likely benefit enormously from AI, in ways that extend far beyond what we have already seen in recent months with productivity, but anyone with eyes can see that there are risks, too.

So it was heartening to see many of the ideas that I have been pushing for a long time, including a CERN for AI and Global AI governance (which I emphasized in April in my TED talk and in The Economist) starting to get traction, and now getting traction from the likes of Yoshua Bengio. Geoffrey Hinton, Daniel Kahneman, and dozens of others.

Indeed, Bengio, Hinton, and others came out a few days ago in favor of much of what both Sam Altman and I advocated for at the US Senate in May, including pre-deployment safety review, auditing, licensing, international governance, and significant funding towards researching AI safety.

Their new proposal in many ways also mirrors what Anka Reuel and I called for in April when we proposed a “global, neutral, non-profit International Agency for AI (IAAI), with guidance and buy-in from governments, large technology companies, non-profits, academia and society at large, aimed at collaboratively finding governance and technical solutions to promote safe, secure and peaceful AI technologies.”

Also dear to my heart, Bengio et al echoed the fundamental theme of this blog:

We need research breakthroughs to solve some of today’s technical challenges in creating AI with safe and ethical objectives. Some of these challenges are unlikely to be solved by simply making AI systems more capable.

§

Many of the arguments I originally gave for a CERN for AI still hold. What I noted in 2017 (at the time focusing on AI for medicine rather on AI safety per se) is that some problems in AI might be too complex for individual labs, and not of sufficient financial interest to the large AI companies like Google and Facebook (now Meta), ehich are after all, driven by profits rather than humanity. That’s still true.

And while every large tech company is making some effort around AI safety at this point, the collective sum of those efforts hasn’t yielded all that much.

We have no way of guaranteeing that large language models will reliably stick to facts, a point so thoroughly established by now I don’t think it needs a reference.

We have no way of guaranteeing that large language models won’t be jailbroken into saying unethical things. To the contrary, a just-published technique shows that current LLMs can be jailbroken quickly, and automatically.

Current AI has no way to reliably anticipate consequences of actions that it might recommend, Asimov’s First Law of Robotics called for robots to do no harm, but current AI has no reliable way to anticipate harm. (Asimov’s laws themselves are insufficient, but if we can’t get the First, how can we believe we are even on track for AI safety at all?).

Anthropic’s “Constitutional AI” idea seems to me to be clever and the best of the bunch, but still inadequate, riddled with the usual problems that LLMs face (reliability, excessive dependence on similarity to what is in the training set, hallucinations, unreliable reasoning, etc). Few other ideas are even on the table.

§

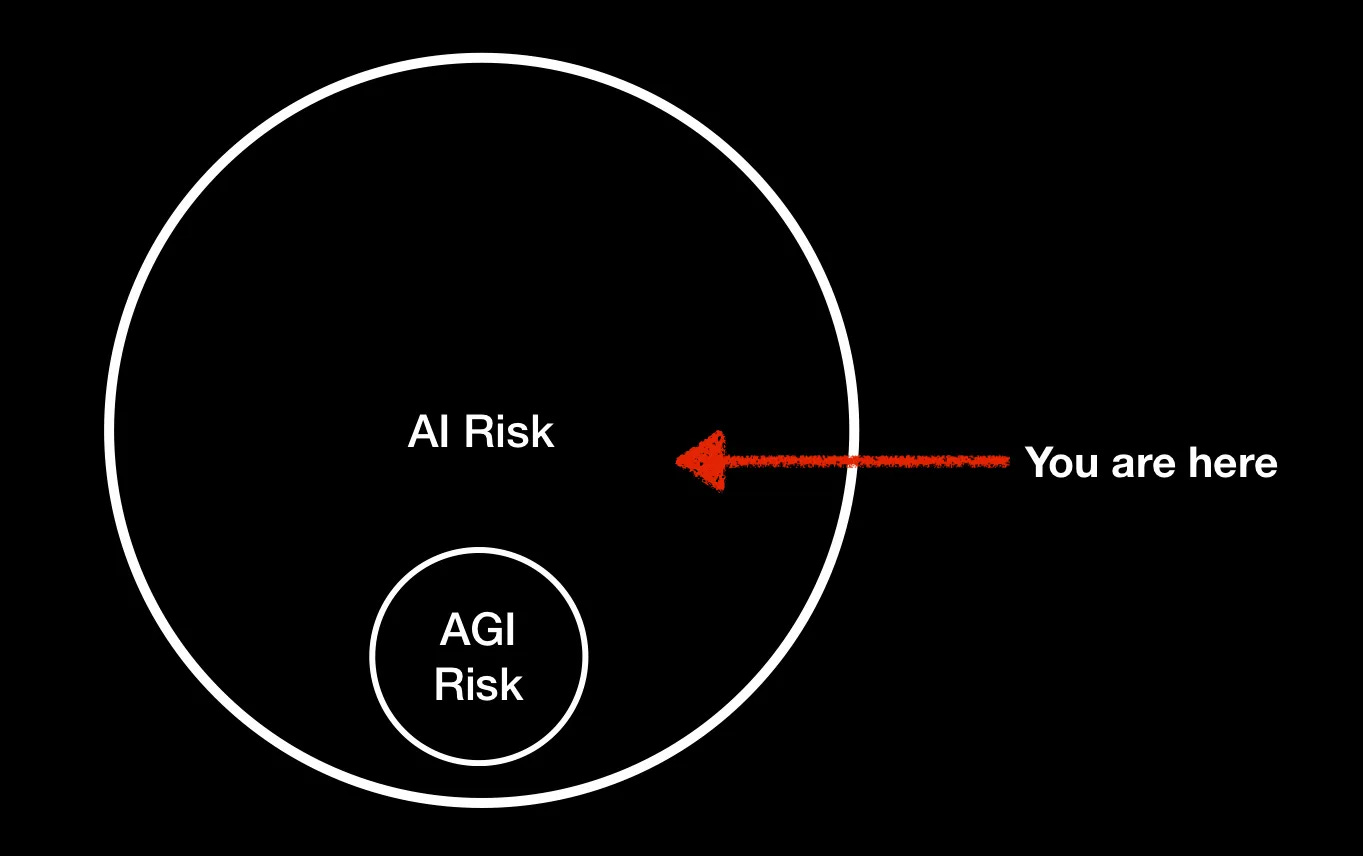

With the UK AI Summit coming up, all the current interest in a CERN for AI Safety and in Global AI is to the good, but there’s something else perhaps worth re-emphasizing, too, which is that the summit appears to be focusing primarily on long-term AI risk – the risk of future machines that might in some way go beyond our control; I think those are legitimate things to worry about, but as I wrote in my March AI risk ≠ AGI risk essay,

“Is AI going to kill us all? I don’t know, and you don’t either… Although a lot of the literature equates artificial intelligence risk with the risk of superintelligence or artificial general intelligence, you don’t have to be superintelligent to create serious problems.The real issue is control. Hinton’s worry, as articulated in the article I linked in my tweet above (itself a summary of a CBS interview) was about what happens if we lose control of self-improving machines. I don’t know when we will get to such machines, but I do know that we don’t have tons of controls over current AI, especially now that people can hook them up to TaskRabbit and real-world software APIs.

We need to stop worrying (just) about Skynet and robots taking over the world, and think a lot more about what criminals, including terrorists, might do with LLMs, and what, if anything, we might do to stop them.

The figure I used to illustrate that point still serves as a handy reminder:

We need to consider both current AI risk and AGI risk. Period.

§

The other thing that should be said is that certain people are hard at work denying that there is any AI risk at all, either long term or short, such as Marc Andreessen, trying to turn the question of whether to pursue AI safety at all into a debate. Don’t listen to them; enormous money is at stake.

You could (as they have) make an argument that the actual harm from AI so far has been modest (a comparatively small number of people have died, for example). But every day brings us closer to a world in which AI causes real harm.

To take but one example, a just-published article asks whether the recent Slovakia election may have been the first to be swayed by deepfakes. The facts on the ground aren’t totally clear, with some arguing that the deepfakes weren’t good enough to fool actual humans. Either way, it’s surely a taste of things to come.. There are over 60 elections around the world in 2024; the chance that at least one will be swayed by deep fakes is high.

§

We can either be like Prometheus or Epimetheus, addressing foreseeable risks before they come, or picking up the pieces afterwards.

Count me among those who continue to favor a CERN for AI safety and Global Safety, so long as we balance the portfolio of risks we are trying to address.

Gary Marcus first proposed a CERN for AI in 2017; he is a techno-optimist who thinks that we can get to an AI-positive world, but that we cannot take such a world for granted.

Kudos for keeping your gloves up and not giving up the fight, the world needs you, it must be frustrating to have seemingly intelligent people in front of you closing their eyes on common sense by pretending that jumping into an unknown of this magnitude without caution could ever be a good idea.

I've been speaking to lots of folks in the AI governance space lately, primarily academics, and I'm struck by how many of them underscore how vital the need is for more research to figure out the nature and scope of many known AI risks. What's also clear is that there's a real schism between those who think the AGI question is helpful even if overstated because it is focusing policy attention and resources on AI risk generally, or whether it's ultimately crowding out the conversation on more immediate, human-driven harms. While I'd like to say "why not both?" there may need to be a reckoning among promoters of trustworthy AI if we are going to make progress.