Many people think that the human mind is the apotheosis of cognition.

I don’t.

For the record, I think the human mind is pretty flawed—and even once wrote a whole book (Kluge) about those flaws. Certainly, more impressive minds than ours could be imagined, and might someday exist.

AI definitely should not aspire to replicate the human mind in every detail. We already have 8 billion human minds, many pretty problematic; we shouldn’t aspire for more of the same.

The point of AI should not be to replicate us, but to supplement us, where we are cognitively frail (calculators are great at that! and spreadsheets! and databases!), and to pitch where we would prefer not to go, helping us, for example, with jobs that robotics call “dull, dirty, and dangerous”.

The Star Trek computer wasn’t a replica of the human mind, it was just everything that LLMs pretend to be. The Star Trek computer was a fantastic spreadsheet-cum-database with encyclopedic knowledge, broad mathematical, synthetic, and inferential abilities, and a kick-ass, hallucination-free natural language interface. That’s what AGI should be: something that solves our problems for us (rather than creating new ones).

§

Humans are very good at a bunch of things that AI is (as of today) still pretty poor at

👉maintaining cognitive models of the world

👉inferring semantics from language

👉comprehending scenes

👉navigating 3D world

👉being cognitively flexible

yet pretty poor at some others (wherein you could easily imagine AI eventually doing better)

👉memory is shaky

👉self-control is weak

👉compute limited

👉subject to confirmation bias, anchoring, & focusing illusions

Eventually, we will be able to build machines that help us reason critically, overcome human bias, and objectively, the way that we have calculators that spit out just the facts, without confabulation. We will build machines that reason more reliably than we do (already the case, but only in limited circumstances), and synthesize information far better than we can.

As it so happens, we aren’t there yet, given our primitive early 21st-century knowledge of AI, and there is a lot of confusion on that point. The brutal truth is that you can’t reason reliably if you can’t maintain cognitive models of the world, no matter how much memory or compute you might have.

§

Every time I give a public lecture, I keep waiting for someone snarky to ask, “Professor Marcus, how could you write a whole entire book about human cognitive errors and still say humans are smarter than machines?”

To my surprise, nobody has.

If they did, here’s what I would say:

Actually, it’s more complicated than that; intelligence is a multidimensional variable.

Machines are actually already light years ahead of humans on some variables (like computing floating point arithmetic), yet way behind on others (like cognitive flexibility and long-term planning in unusual situations). And, really, machines themselves have a kind of cognitive diversity: each algorithm has its own strengths and weaknesses, LLMs are great at some kinds of pattern matching, but lousy at floating point arithmetic. Calculators are great at floating point math, but generally don’t do much pattern matching at all. The secret to making AGI almost certainly rests on getting disparate algorithms (e.g., those that work well with symbolic knowledge, those that can induce regularities from massive amounts of unstructured data, etc) to work together well.

For now, humans aren’t more intelligent than machines or vice versa, we are just differently abled. As Ali G once said in a different context, “neither is better”.

§

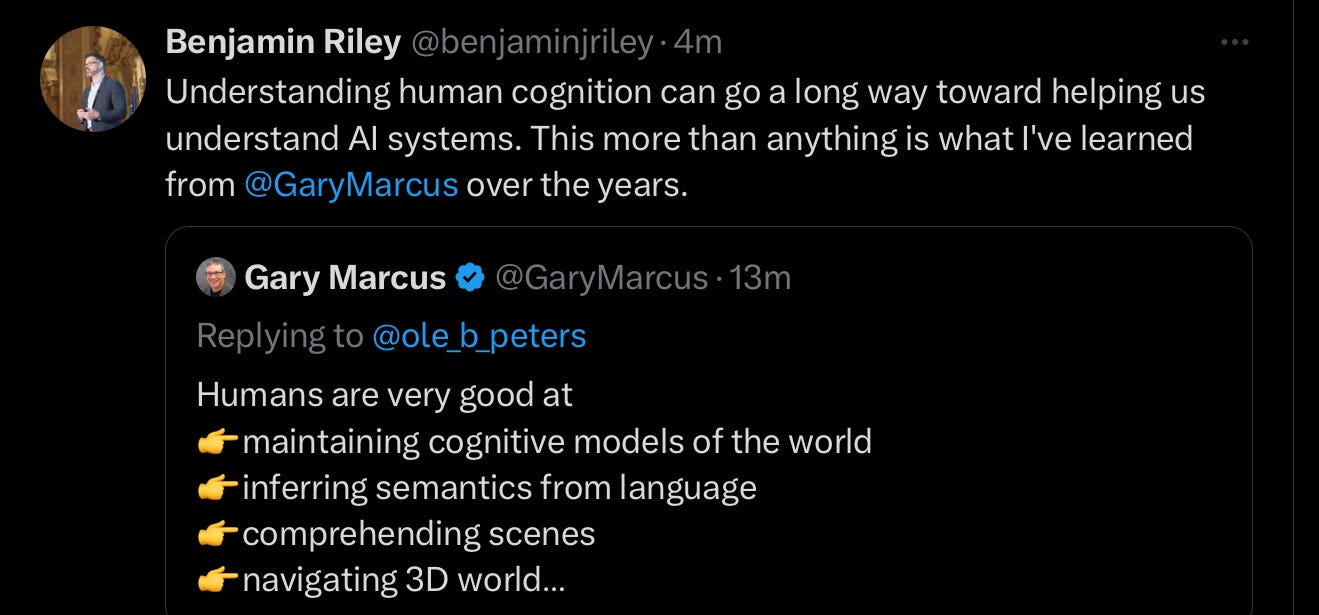

This tweet made my day:

It made my day because that’s what I’ve been trying to teach everyone, for a long time: we can probably make machines better if we spend time first thinking about human minds (both their strengths and their weaknesses).

It’s not a competition. It’s not that we have a horse race here, with either humans or machines are inherently better. My podcast (Humans versus Machines wasn’t really about judging a winner, it was about comparing the two, and seeing what we could learn from the comparison— teasing out the implications that derive from those differences, for things like driverless cars, humor, medicine, jobs, and AI policy.

The sooner we realize that humans and silicon machines are importantly different, the better.

Gary Marcus sees a lot of natural and artificial stupidity, more or less every day, but sincerely hopes that we can use insights from natural intelligence to make artificial intelligence better.

Deep breath.

As a former special education professional who worked a LOT with cognitive assessments, and spent many hours correlating cognitive subtest scores with academic performance in order to create learning profiles, do I ever have an opinion on this.

Too many people are simply unaware of the complexities of human cognition. I've seen how one major glitch in a processing area...such as long-term memory retrieval (to use the Cattell-Horn-Carroll terminology) can screw up other performance areas that aren't all academic. Intelligence is so much more than simply the acquisition and expression of acquired verbal knowledge (crystallized intelligence) that tends to be most people's measure of cognitive performance. I have had students with the profile of high crystallized intelligence, low fluid reasoning ability and...yeah, that's where you get LLM-like performance. The ability to generalize knowledge and experience, and carry one learned ability from one domain to another is huge, and it is not something I've seen demonstrated by any LLM to date. I don't know if it is possible.

Unfortunately, too many tech people working on A.I. haven't adequately studied even the basics of human cognitive processes. Many of those I've talked to consider crystallized intelligence to be the end-all, be-all of cognition...and that's where the problems begin.

This is one of your better posts. Thank you.