In a new episode of his podcast with Ben Buchanan former special adviser for artificial intelligence under Biden, entitled, The Government knows A.G.I. is coming, The New York Times’ usually fabulous Ezra Klein declares with too much certainty that AGI is pretty much imminent, and urges you to get with the program.

He goes on to argue that this transformation will be enormously important. (“If you’ve been telling yourself that this isn’t coming, I really think you need to question that … There’s a good chance that, when we look back on this era in human history, A.I. will have been the thing that matters.”)

There is a lot to like in the episode. I completely agree with Klein that AGI will matter a lot when it comes. He rightfully acknowledges that we dont’t really know what the AGI era will look like. Buchanan makes some great comments on the too-loose security around AI at San Francisco house parties, and why that might be a problem. And I totally loved that Buchanan warned, rightly, that there is “a risk of a fundamental encroachment on rights from the widespread unchecked use of A.I.” Buchanan also made terrific points about why safety regulation was a positive, not a negative, for the early railroad industry. And there is plenty of inside insight into what the Biden administration was thinking.

But I think that Klein is dead wrong about the AGI timeline, around which a fair bit of the episode rests. I think there is almost zero chance that artificial general intelligence (which his podcast guest reasonably defines as “a system capable of doing almost any cognitive task a human can do“) will arrive in the next two to three years, especially given how disappointing GPT 4.5 turned out to be.

But it is not just that I think Klein is wrong, or that he did a disservice to the other side of the argument, but that words like his are motivating a lot of dodgy bets being placed on the imminent AGI assumption — in ways that may not make sense.

§

Before I get to my own take, and why I think Klein did a disservice to the alternative, I want to address something that the ever-optimistic Wharton Professor Ethan Mollick wrote re: Klein’s statement, on X:

It’s always great to position yourself as the underdog, but is it really true that leaders and policymakers aren’t considering the possibility that AGI is “a real possibility in the near future”?

To start with Klein’s own podcast features Ben Buchanan, Biden’s top AI expert, basically endorsing the “real possiblity in the near future” option throughout the interview. Of course Biden is gone and Trump is in, but Musk is arguably Trump’s AI top expert, and he’s endorsing it, too, as I imagine is Musk’s friend David Sacks, who is Trump’s official AI czar (essentially replacing Buchanan). That’s a pretty strong reach in the government right there. Then we have “AGI is imminent” industry CEOs like Sam Altman, Musk himself (founder of X.ai), and Dario Amodei, not to mention podcasters like Kevin Roose and Casey Newton at the Times. NYT Op-ed columnist Tom Friedman also seems to think AGI is imminent. Practically every doomer from Max Tegmark to Eliezer Yudkowsky seems to think the same. Both the British and US governments set up research centers largely on that premise. Which is not say that everybody believes AGI imminent or cares or spends every waking hour contemplating that notion. A lot of old-school AI people would probably tell you that the idea is ridiculous. Some, like Melanie Mitchell think that talk of AGI is all hopelessly vague. But it is absolutely absurd to pretend “AGI imminent” hypothesis isn’t getting play in high places.

§

Nonetheless, for reasons I will articulate shortly, I do think that the hypothesis that AGI is imminent almost certainly wrong.

And, importantly, the reverse of what Mollick said is also true: we have to consider the scenario that the proposition that AGI is imminent is false. And if there is any scenario that is underrepresented in current policy discussions, it’s that one. Honestly, until recently perhaps the only major pundit who didn’t seem to buy into all this was Ezra Klein, himself, who two years ago was not a true believer, saying in one of his podcasts that a lot of LLM outputs were “surprisingly hollow, or maybe a little bit worse than that”. He even went on to analogize their output to bullshit, “in the classic philosophical definition by Harry Frankfurt” adding that “It is content that has no real relationship to the truth.” I miss the old Ezra.

The new Ezra is far less skeptical. (The low point was when Klein said it was “slightly damning” that the Biden administration didn’t use Claude, presumably a security risk like all LLMs, to write its confidential memos.)

Aside from mentioning a recent positive experience with Deep Research, Klein didn’t fully articulate why he was convinced AGI is likely imminent, beyond saying that folks in industry and government tell him so. (My view, as I explained in Taming Silicon Valley, is that industry has a vested interest in making people believe that AGI is imminent — how else to justify the lavish valuations - and that they have fooled a lot of people in government who aren’t technical experts into believing that AGI is closer than it really is).

§

Why is my timeline longer than Klein’s? Because (a) I have learned to discount industry hype and (b) as a cognitive scientist, I look at what we have, and it’s still missing a lot of prerequisites, like these:

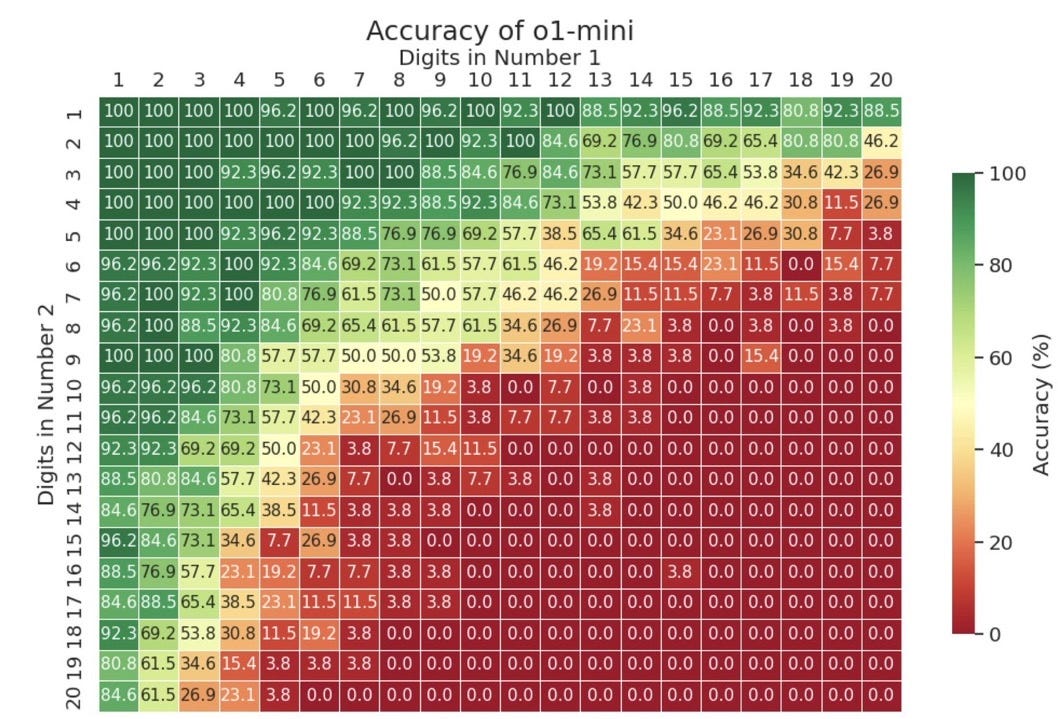

• AGI should have a reliable ability to freely generalize abstractions to new instances regardless of how similar they are to items encountered in training. Apple’s recent study formal reasoning very much confirms that this is still not the case, more than two decades after I first pointed out this weakess. Another recent study on multiplication, replicates the weakness once again. even with the recent model o1-mini.1 Every red cell in this graph (e.g, multiplying 20 digit numbers by 19 digit numbers2) is failure to generalize, even after immense amounts of training data:

On a good scientific calculator, every single number would be in green.

• AGI should have reliable ability to reason over abstractions. (Ongoing unpredictable errors in LLMs reflect this.)

• AGI should have a reliable ability to keep track of individuals and their properties without hallucination. (Hallucinations simply haven’t gone away, even in the latest models. The occasional bizarre violations in object permanence in models like Sora are another reflection of this )

• AGI should have a reliable ability to understand complex syntactic and semantic structure. (Failings here are also often reflected in quirky errors. Just-reported empirical work by Elliot Murphy and colleagues including myself confirms this)

What’s especially notable about that list is that is exactly the same as the list I outlined in my first book, The Algebraic Mind, which was published in 2001, and written the year before.

What that means is that a quarter century has passed without a principled solution to even one of those problems.

§

That really only leaves three possibilities.

Everything will be solved everywhere at once. We will go from 33% hallucinations (per one particular recent measure, though mileage varies quite a lot across contexts) to more or less zero, more or less overnight; erratic errors, same thing; poor planning, solved; etc etc. Generalizations will become vastly more reliable, and so on. How on earth will we do this so fast? While it is not logically impossible that all this could happen so quickly, this theory (or should I call it “this hope”) seems to me like the immortal Sydney Harris cartoon, two scientists peering at equations at blackboard, “..and then a miracle occurs”. Especially when we just saw GPT-5 (ultimately relabeled as GPT 4.5) fail despite more than two years of hard and expensive work.

Everything won’t be solved everywhere all at once; getting to AGI will be a slog. Some problems will be solved in the next 2-3 years, but others won’t. Some will take longer.

Achieving AGI is impossible, and we will never get there.

Having observed the pace of science and engineering firsthand over the last half century, the middle scenario seems to me like – by far – the most plausible. A set of problems that have resisted solution for a quarter century, even backed by a half trillion dollars, probably aren’t all going to get solved so quickly. A solve for even one would be ground-breaking.

But there’s also no reason to think that any of them are logically insolvable in principle. So we will get there someday. But it is like thinking that the earth is at the center of the universe to think that it will all happen right now just where we are standing, just because LLMs are more impressive than many people initially expected.

§

Speculating about the arrival of AGI used to be just an “academic” question, a curiosity for philosophers and other interested parties to contemplate, but it is no longer. Instead AGI timelines are (a) the focus of some of the largest investments in history and (b) at the center of an enormous number of very delicate policy questions, which is really what the recent Klein-Buchanan episode is ultimately about.

What made me gnash my teeth is that both parties (both of whom I like and have spoken with) did the opposite of what Mollick suggested: they didn’t really consider all scenarios. They (more Klein than Buchanan) mostly just assumed that AGI is imminent, discussed policy questions based on that assumptions. Almost all the potential counters to that notion were never even considered.

In a long podcast, that is otherwise very au courant, with discussion of the Trump administration, Deep Seek, and so on, Klein and his guest never discussed for example

Reports from The Wall Street Journal and Fortune that Project Orion, which was supposed to yield GPT-5 was behind schedule and disappointing.

Comments from industry insiders like Satya Nadella and Marc Andreessen that seem to indicate that pure scaling of training and compute has reached diminishing returns.

The fact that Nadella has acknowledged that the current impact of AI on GDP has been minimal.

The fact that Orion appears to have been downgraded, ultimately released under the name GPT 4.5 rather than 5.

The fact that GPT 4.5 received very mixed reviews — despite years of labor and billions investment — and could in no reasonable way be considered a major (rather than minor, incremental) step forwards towards AGI.

The fact that GPT 4.5 is wildly expensive relative to its competitors, and the fact that future models following the same trajectory of scale might be prohibitively expensive, especially in a regime in which nobody has a moat and price wars have been intensifying since the release of DeepSeek. (As I posted this, the Information reports OpenAI is hoping to get $20,000/month for its best agents).

The fact that Grok 3 was 15x the size of Grok 2, and also generally viewed as disappointing.

The fact that some reviews of Deep Research and Grok 3 Deep Search are quite scathing, with both systems plagued with the same hallucinations and reasoning errors etc we’ve seen so often before. Automatically generated bullshit still seems to be the norm. Colin Fraser told me that (in his admittedly adversarial testing) that o3 “[often] bounces around randomly, making stuff up, pretending to be looking for an answer, but it is not actually attracted to correct answers in the way that a goal-oriented agent would be” and that “every time I’ve tested it on something that is verifiable, it has failed miserably”. And these complex systems, built on the unreliable foundations of LLMs, are going to prove to be massively difficult to debug.

Studies from places like Apple and academics like

showing ongoing troubles with reasoning, like a just-published article that reports “despite previously reported successes of GPT models on zero-shot analogical reasoning, these models often lack the robustness of zero-shot human analogy-making, exhibiting brittleness on most of the variations we tested.”The fact that even the most optimistic reviews of Deep Research still acknowledge that current systems still do not exhibit “signs of originality”. There is a long, long, long way from writing basic reports to the kind of AI that could match the originality of top human scientists. AI might replace average people in some tasks soon; replacing the best humans in a few years? Not going to happen.

The long history of overpromising in the industry is never mentioned. Most parts of the US still don’t have functioning driverless cars systems, for example, even after over a decade of lavish promises. Heavily-AI dependent products like the Humane AI Pin died on the vine. Hallucinations haven’t solved, despite constant assurances. And so on. As Ben Riley put it, in his own review of yesterday’s podcast, “Delusional, overconfident predictions about AI have been occurring with regularity since the dawn of AI itself”.

I could go on, but you get the point. Klein’s presentation of the imminence of AGI was not balanced with any serious review of the many arguments that might cast doubt on that assertion.

That’s really not what I have come to expect from Ezra Klein.

To Buchanan’s credit, towards the end of the intervieww he actually gently pushes back against Klein’s near-dogmatic certainty. After Klein claims that AI the “most transformative technology — perhaps in human history — is landing in a two- to three-year time frame “, Buchanan responds, and I salute him for this, “I think there should be an intellectual humility here. … it is entirely intellectually consistent to look at a transformative technology, draw the lines on the graph and say that this is coming pretty soon, without having the 14-point plan of what we need to do in 2027 or 2028.”

Buchanan closes (before Ezra’s signature “name 3 books” ending) with “I think there really are a bunch of decisions that they are teed up to make over the next couple of years that we can appreciate are coming down the horizon without me sitting here and saying: I know with certainty what the answer is going to be in 2027.” Bravo!

I really wish Klein (ordinarily one of the world’s best listeners) had better taken Buchanan’s note here.

[Update: in an email to me Ezra Klein suggested I may have misinterpreted Buchanan’s meaning here, with Buchanan being more focused on uncertainty around what we should do than around uncertainty about timing. Klein may well be right, there, though I still think we should take Buchanan’s point about intellectual humility and uncertainty more broadly.]

§

The reason it matters is that the very policies that Klein and Buchanan discuss throughout the episode — like export controls on chips and investments in massive infrastructure that will come at considerable cost to the environment— rest almost entirely on the assumption that AGI is nigh, and that LLMs will get us there.3 But what if they don’t get us there?

If LLMs are the wrong path to AGI, as I and a great many academics think, we may have a lot of thinking to do. We may be massively wasting resources, and getting locked into a lot foolish battles around the wrong technology.

The thing that was most missing from the interview was any discussion of research. If getting to AGI in the next three years is not quite as certain as the sun rising every day from the east, we might want to hedge our bets, and try to focus on what the field of AI need to develop besides scaling. I was quite disappointed to see the notion of research get essentially no mention. In a time when Trump is dismantling American research infrastructure, it should have been front and center.

When I read later yesterday that a Chinese group had just done some clever and potentially important work off the beaten path, in neurosymbolic AI, the undersold form of AI that I have long advocated, I couldn’t help but think that the US’s single-minded commitment to Large Language Models, predicated on implausible assumptions about AGI’s imminence, particularly combined with the untimely gutting of its scientific institutions, could ultimately lead to its undoing.4

Gary Marcus genuinely loved appearing on the Ezra Klein show two years ago would certainly be glad to return to discuss the slowdown of pure scaling and what that might mean for how to think about AI policy.

One could fairly argue that there has been some progress. The same study shows o1 is better at this task than GPT 4o. But it’s not entirely meaningful comparison to the extent that o1 has likely received specific training on mathematics as part of its data augmentation. More importantly, even with extra augmentation, the system remains wildly unreliable on tasks that many systems have been able to handle for decades.

Some will say “humans make arithmetic errors, too”, but AGI really shouldn’t. If it is this unreliable on arithmetic, it will be this unreliable on everything else, and we shouldn’t accord it the society-changing power that people intend to accord it. Arithmetic is interesting here not because humans are good at it but because it provides a direct way to test generalization. In many more complex domains, we as scientists are hampered in studying LLMs because the companies that make them don’t share the training data or full system diagrams. As such it is very difficult to know the degree to which any given answer is true generalization versus regurgitation, perhaps with small changes. The point here is not about arithmetic but generalization.

Another implicit assumption is that getting to AGI first, even by a few months, will matter a lot. This might be true, but it might be not. There is a notion implicit in the interview that whoever gets to AGI first will have some massive advantage. But what will that advantage be? Klein’s guest Buchanan argues, for example, there will be “profound economic, military and intelligence capabilities that would be downstream of getting to A.G.I. or transformative A.I. And I do think it is fundamental for U.S. national security that we continue to lead in AI”, but the interview is short on detailed scenarios. Would a six month lead become a permanent advantage due to some uncopyable, undefeatable superweapon? Or just a modest uptick in GDP? I am not convinced that anything anyone could realistically do with LLMs won’t be almost immediately copied, as has been the recent trend. (I do 100% agree with Buchanan though in his remark that “there is a fundamental role for America here that we cannot abdicate.” It was depressing that Trump scarcely mentioned AI last night, except in connection to an investment that Elon himself has described as dubious and overleveraged.)

Things get even worse when you factor in the recent dismantling of academic research institutions (never mentioned in the episode), along with a President hellbent on increasing manufacturing jobs rather than fostering science. It actually seems to me that US may be all but surrendering the AGI race over to China.

"On a good scientific calculator, every single number would be in green."

So many have argued over this recently. Critics often will say, "well I can't do that in my head". That's right, you would ask for calculator, because you have self-reflection for your abilities and understanding for the tools that provide those abilities.

This led me to write "Why Don't LLMs Ask For Calculators?" - https://www.mindprison.cc/p/why-llms-dont-ask-for-calculators

It is another simple example that completely exposes the lack of any reasoning. Do LLMs know that they are bad at math? Yes. They will state so, based on their training of course. Do LLMs know what a calculator is? Also Yes. And they still can't place these two concepts together to realize they are likely giving your wrong answers.

Again I ask, why is the goal to make AI as smart as humans? As CEO of an intelligent robotics company, my question was similar: why make androids? The point of automation is to solve problems. General purpose humans, or general purpose human brains, are hardly the best solutions to human problems, or market opportunities. It's like building a mechanical super-horse instead of inventing a Tesla.

Even for the transhumanists seeking to build the next generation human 2.0, the basis for evolutionary symbiosis between two entities is a division of labor. We should be figuring out which jobs AI and humans each excel at and transitioning toward a symbiont that combines the two (or three, if including robotics.)