Form, function, and the giant gulf between drawing a picture and understanding the world

Tools like Stable Diffusion and Dall-E are inarguably brilliant at drawing images. But how well do they understand the world?

Drawing photorealistic images is a major accomplishment for AI, but is it really a step towards general intelligence? Since DALL-E 2 came out, many people have hinted at that conclusion; when the system was announced, Sam Altman tweeted that “AGI is going to be wild”; for Kevin Roose at The New York Times, such systems constitute clear evidence that “We’re in a golden age of progress in artificial intelligence”. (Earlier this week, Scott Alexander seems to have taken apparent progress in these systems as evidence for progress towards general intelligence; I expressed reservations here.)

In assessing progress towards general intelligence, the critical question should be, how much do systems like Dall-E, Imagen, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion really understand the world, such that they can reason on and act on that knowledge? When thinking about how they fit into AI, both narrow and broad, here are three questions you could ask:

Can the image synthesis systems generate high quality images?

Can they correlate their linguistic input with the images they produce?

Do they understand the world that underlies the images they represent?

On #1, the answer is a clear yes; only highly trained human artists could do better.

On #2, the answer is mixed. They do well on some inputs (like astronaut rides horse) but more poorly on others (like horse rides astronaut, which I discussed in an earlier post). (Below I will show some more examples of failure; there are many examples on the internet of impressive success, as well.)

Crucially, DALL-E and co’s potential contribution to general intelligence (“AGI”) ultimately rests on #3; if all the systems can do is in a hit-or-miss yet spectacular way convert many sentences into text, they may revolutionize the practice of art, but still not really speak to general intelligence, or even represent progress towards general intelligence.

¶

Until this morning, I despaired of assessing what these systems understand about the world at all.

The single clearest hint that they might have trouble that I had seen thus far was from the graphic designer Irina Blok:

As my 8 year old said, reading this draft, “how does the coffee not fall out of the cup?”

§

The trouble, though, with asking a system like Imagen to draw impossible things is that there is no fact of the matter about what the picture should look like, so the discussion about results cycles endlessly. Maybe the system just “wanted” to draw a surrealistic image. And for that matter, maybe a person would do the same, as Michael Bronstein pointed out.

So here is a different way to go after the same question, inspired by a chat I had yesterday with the philosopher Dave Chalmers.

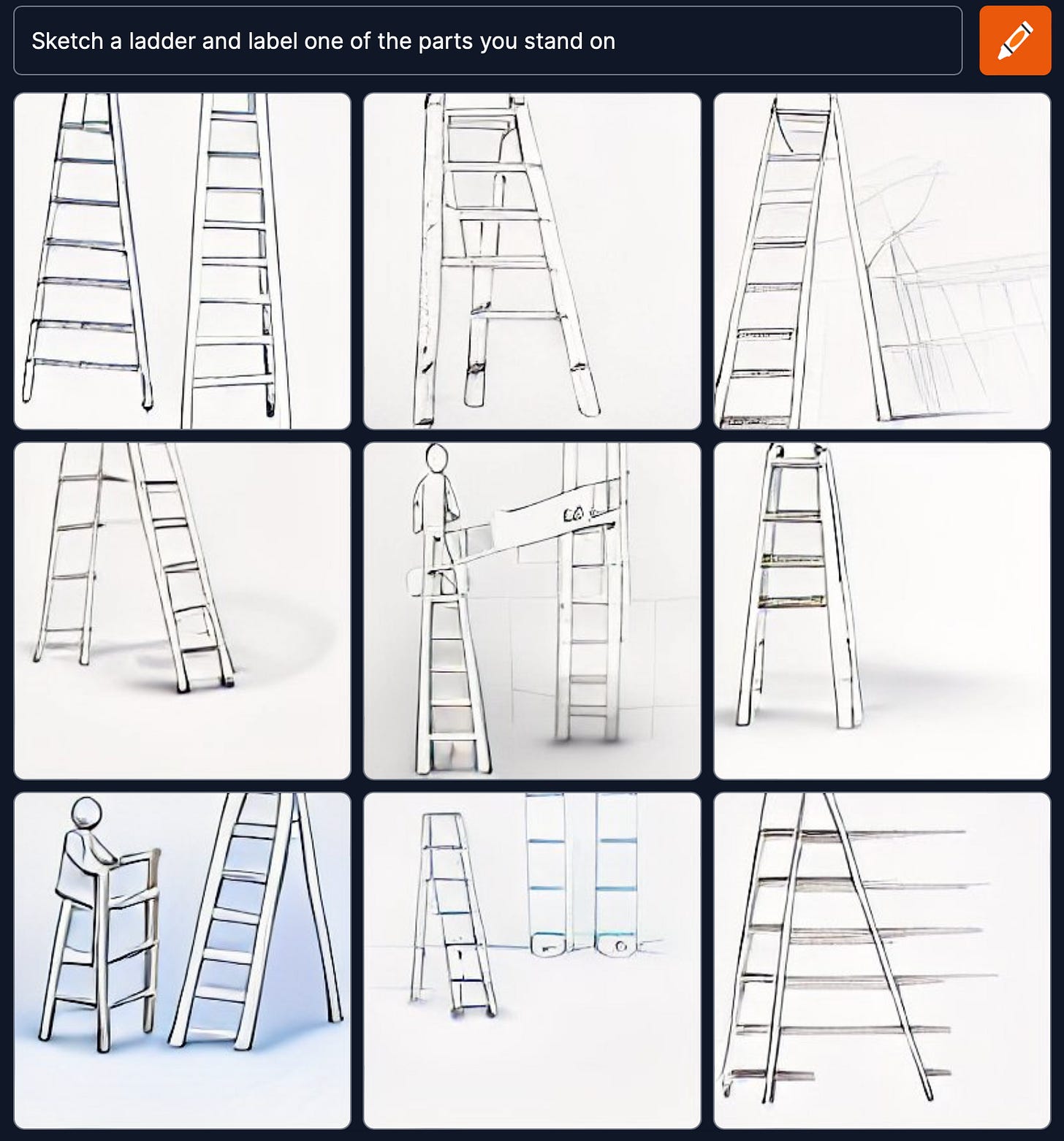

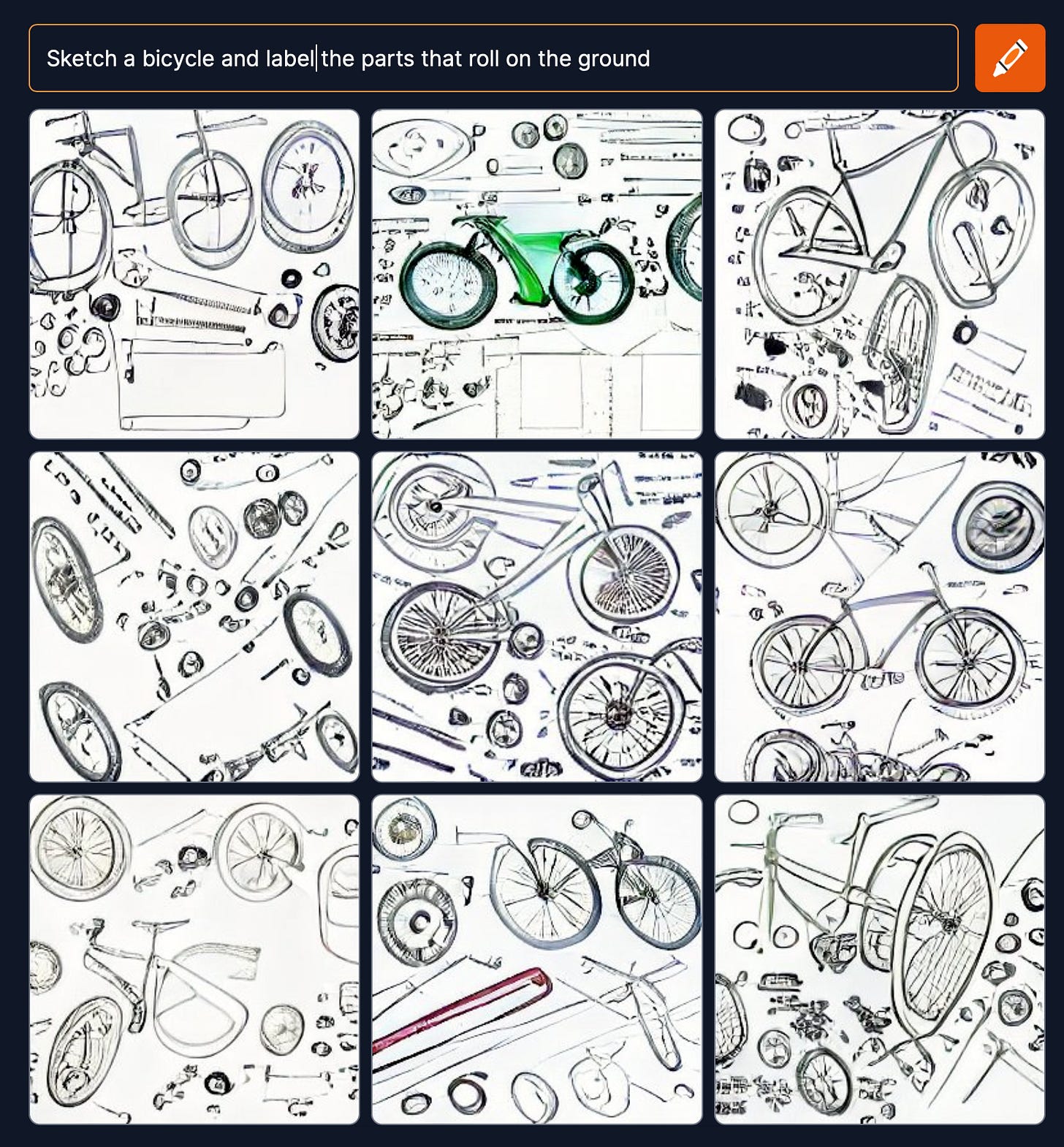

What if we tried to get at what the systems knew about (a) parts and wholes, and (b) function, in a task that had a clearer notion of correct performance, with prompts like “Sketch a bicycle and label the parts that roll on the ground”, “Sketch a ladder and label one of the parts you stand on”?

From what I can tell Craiyon (formerly known as a DALL-E mini) is completely at sea on this sort of thing:

Might this be a problem specific to DALL-E Mini?

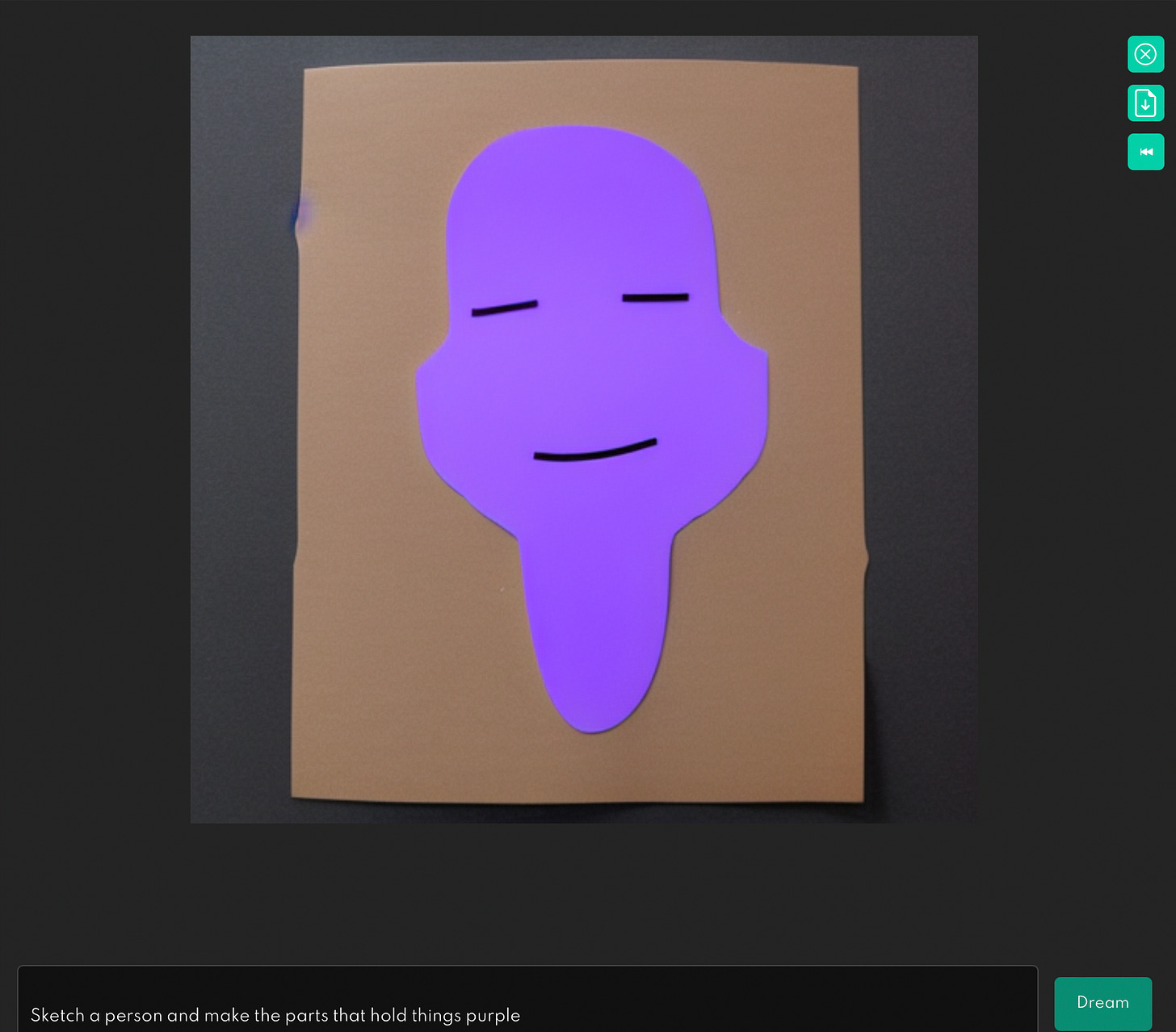

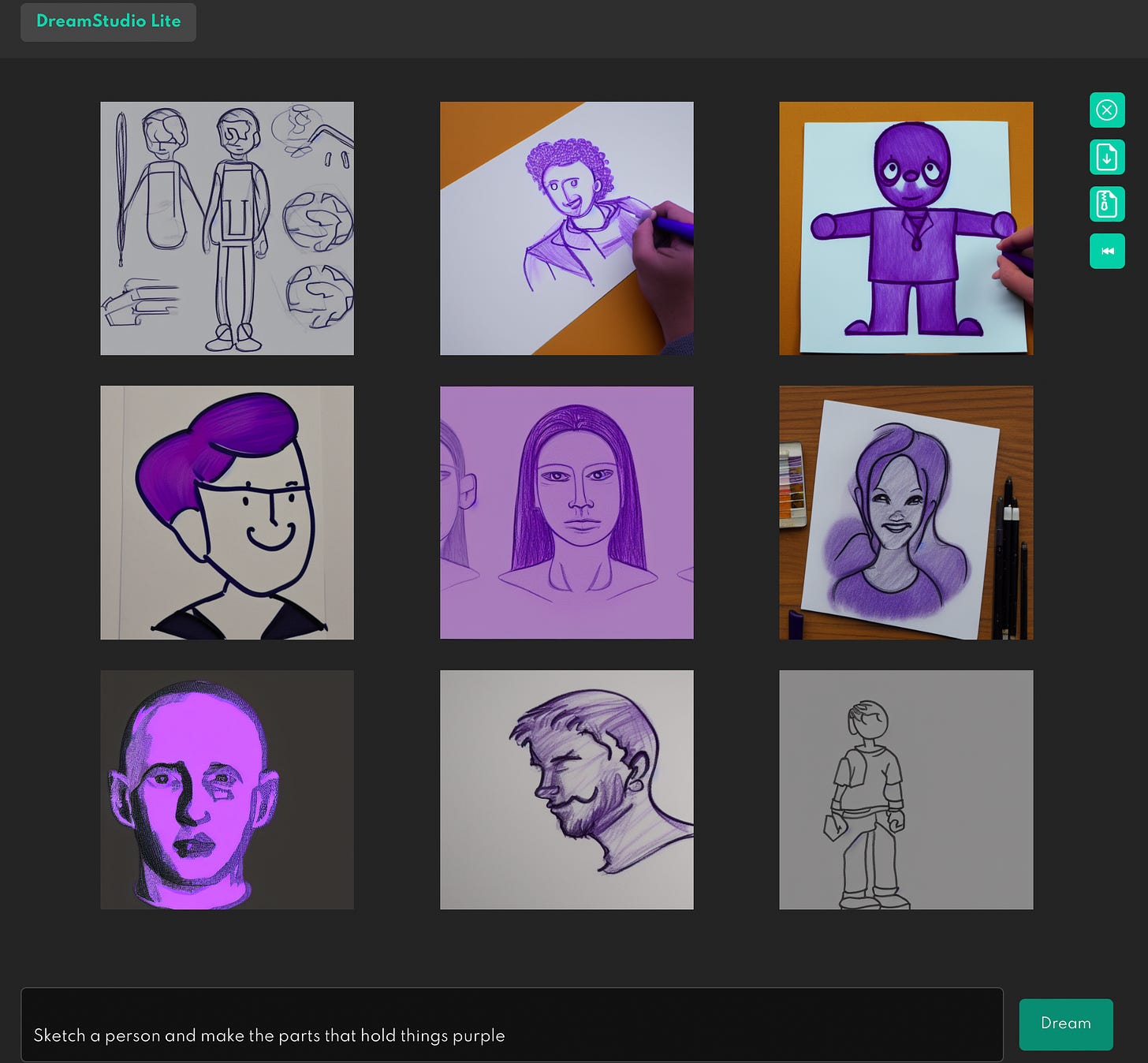

I found the same kinds of results with Stable Diffusion, currently the most popular text-to-image synthesizer, the crown jewel of a new company that is purportedly in the midst of raising $100 million on a billion dollar valuation. Here, for example is “sketch a person and make the parts that hold things purple”,

Nine more tries, and only one very marginal success (top right corner):

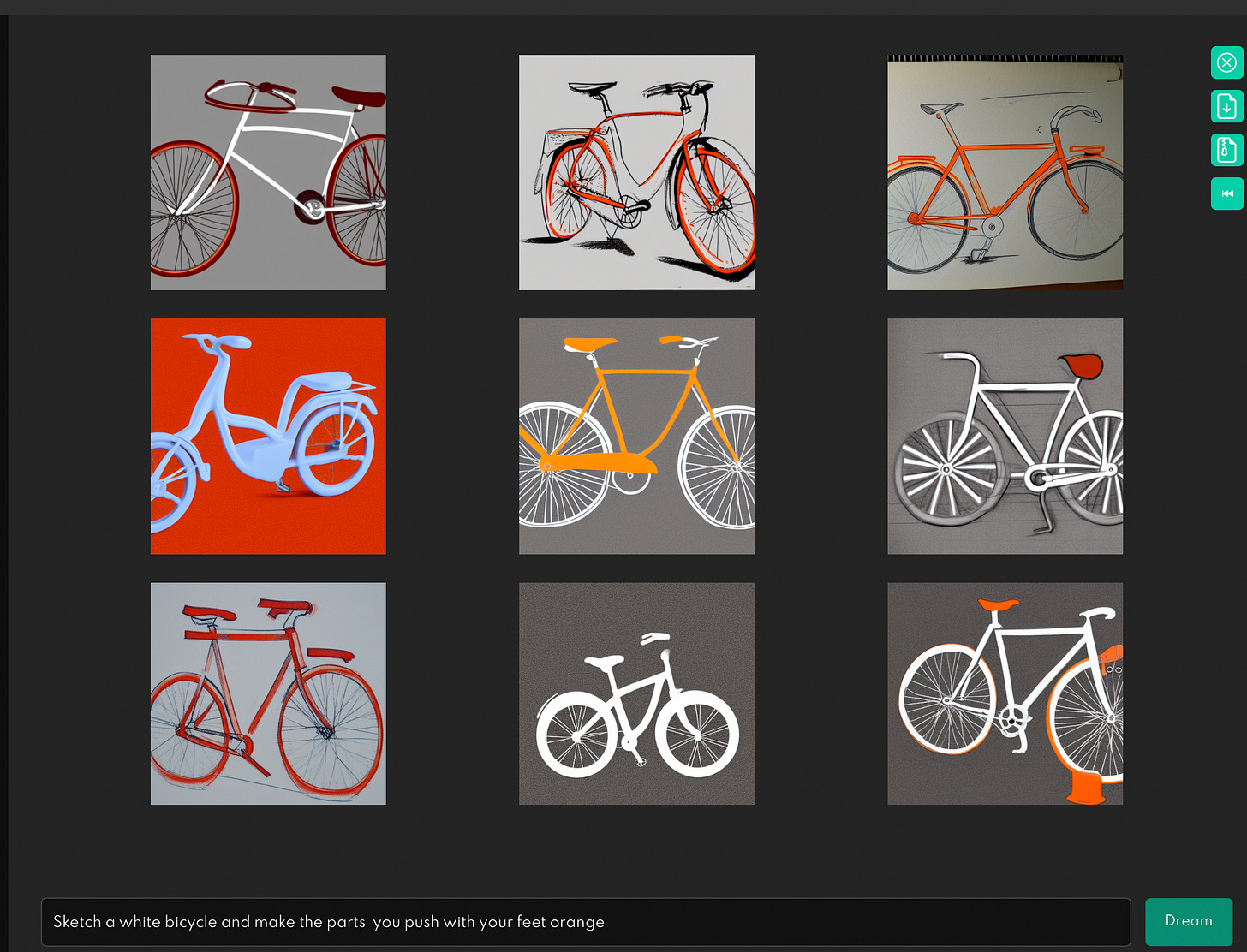

Here’s “sketch a white bike and make the parts that you push with your feet orange”.

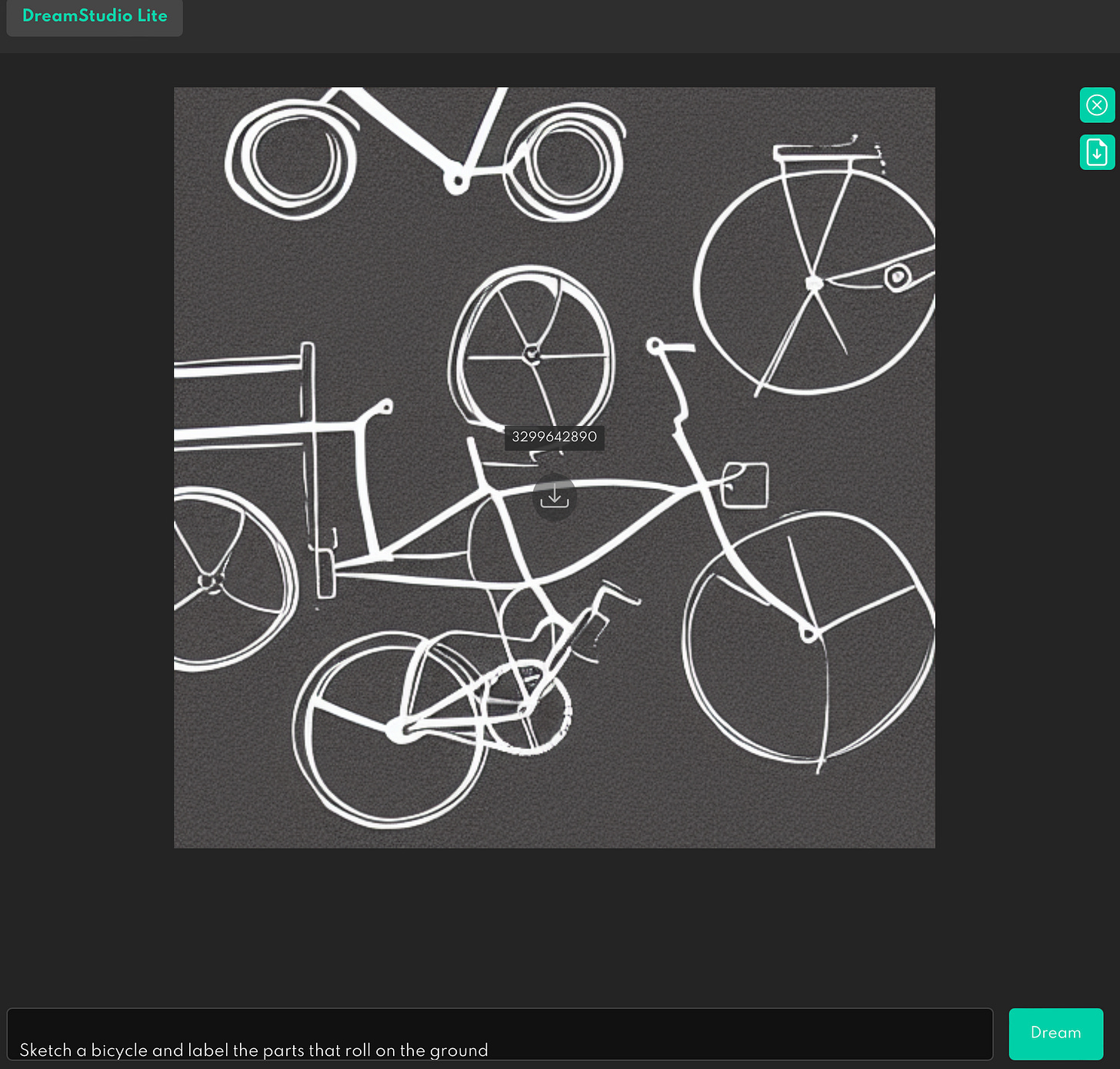

“Sketch a bicycle and label the parts that roll on the ground”

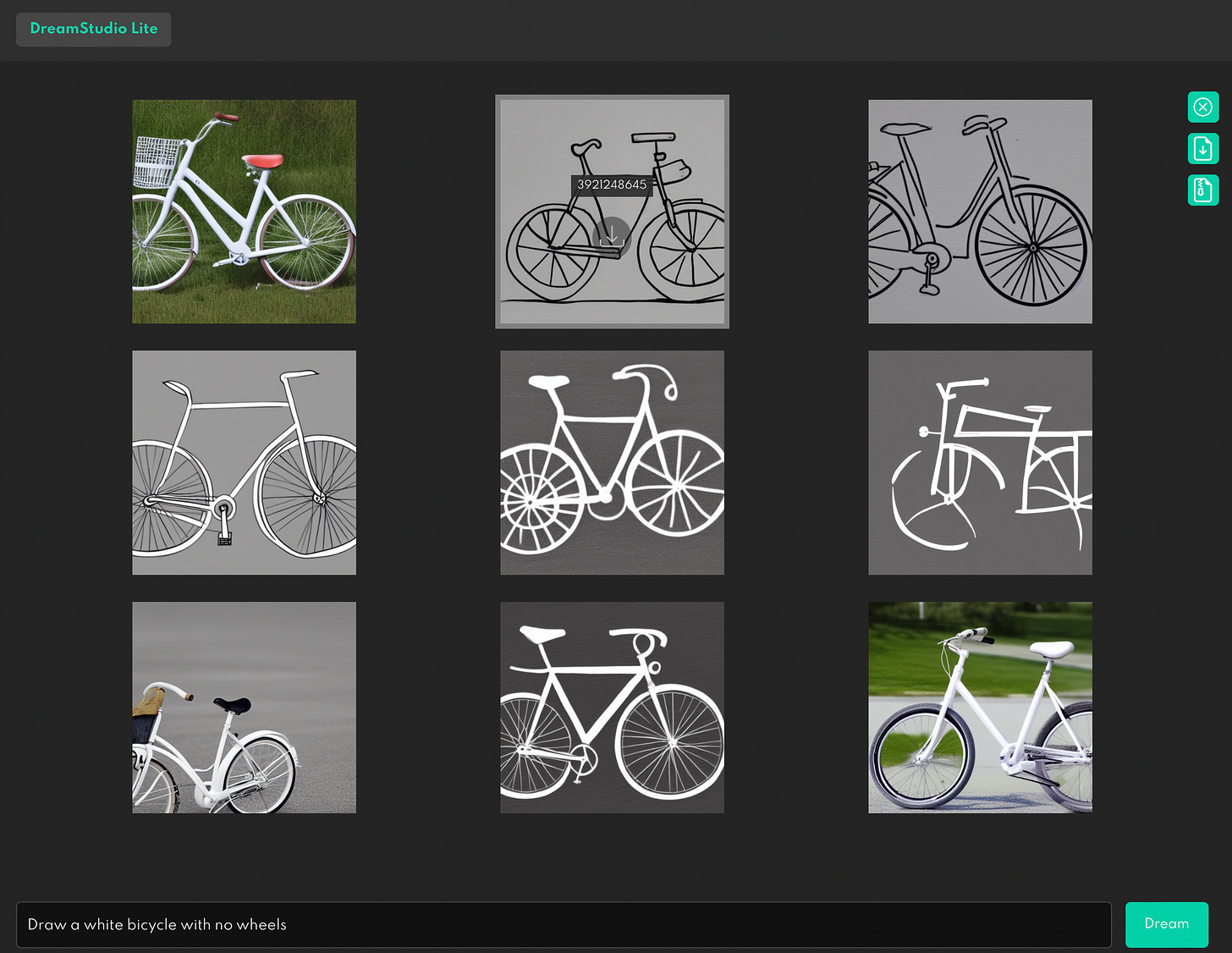

Negation is, as ever, a problem. “Draw a white bicycle with no wheels”:

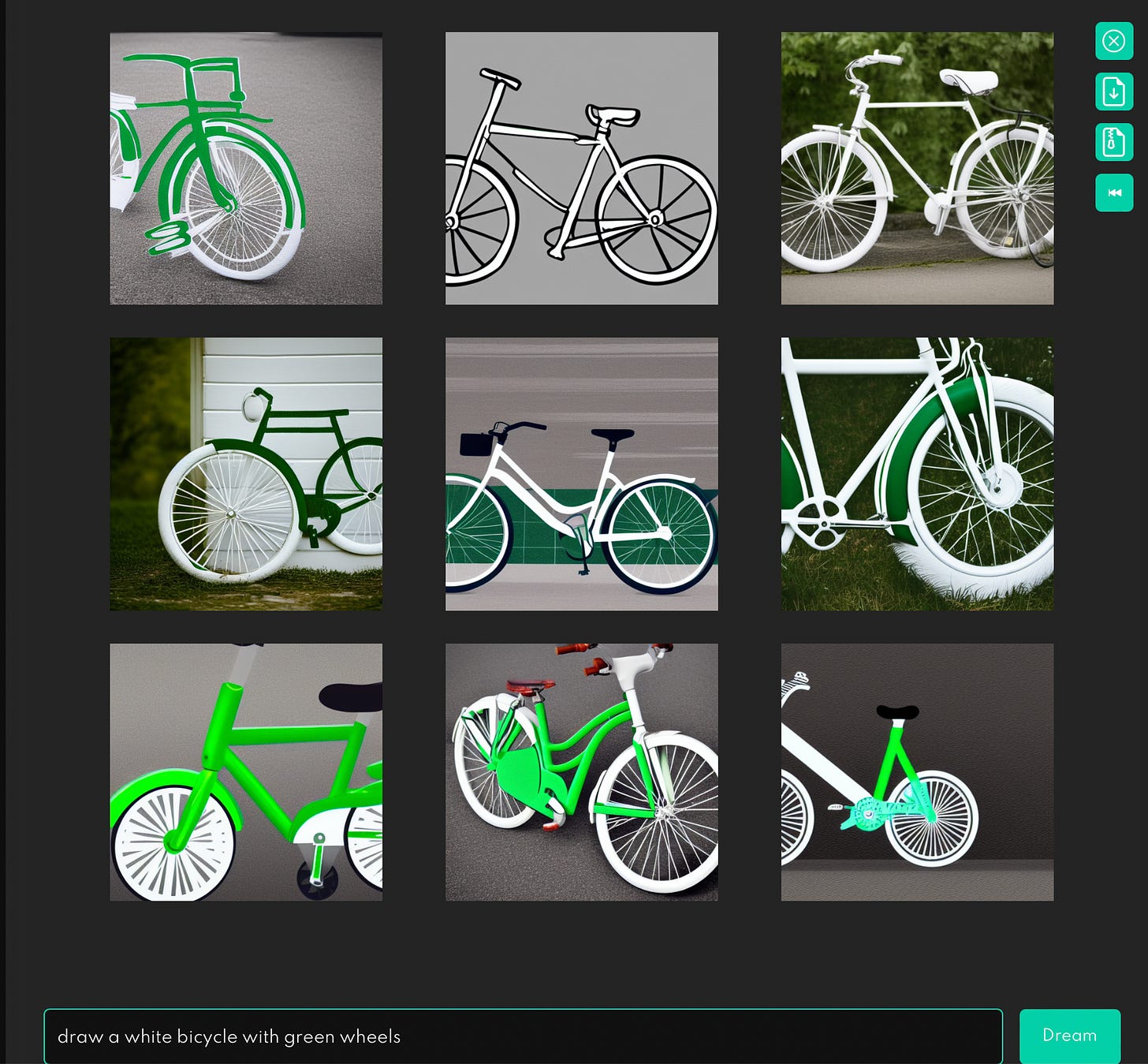

Even “draw a white bicycle with green wheels”, which focuses purely on part-whole relationships without function or complex syntax, is problematic:

Can we really say that a system that doesn’t understand what wheels are—or what they are for—is a major advance towards artificial intelligence?

§

Coda: While I was writing this essay, I posted a poll:

Moments later, the CEO of Stability.AI (creator of Stable Diffusion), Emad Mostaque, offered wise counsel:

A clear and concise article that really cuts through the hype. To say that the efforts are "part of the puzzle" is to imply that they already have one of the correct pieces to slot in. That's a bold claim that requires justification. I'd imagine you'd have better intepretive results if you asked a 5 year old kid with a set of colouring pencils. I'd like to see AI"'s formally age graded against humans. I'm still waiting for that scrap of solid evidence that they're anything but parlour trickery.

What's fascinating to me is that, despite having seen probably millions of bicycles (certainly more than I ever have), these image generators still do things that leave off chains, blur together the pedals and frame, and create wheel spokes in patterns that would never appear on a real bike (because they'd never work). This isn't even a matter of understanding the world; this is sheer failure to properly regurgitate training input when the pattern gets a little complicated. You see little things like this in almost every AI generated image when you look closely enough. We recognize immediately that these bicycles or coffee cups or squirrels don't look quite right. Why can't an AI?