Learning Language is Harder Than You Think

Sure, kids imitate their parents, but that’s just a small part of the story

If only acquiring language was easy some in the AI Twitterverse seemed to think. Take this Tweetstorm the other day, from David Chapman:

Roughly 1,000 people liked the first tweet in Twitter thread, probably because they want to feel like they are smarter than Noam Chomsky. Spoiler alert: they probably aren’t.

As the rest of the thread goes on to explain, the alluring premise is that learning language is simple; all a child really needs to do is to memorize a bunch of stuff, and then copy and paste the memorized bits. (Implied bonus: systems like GPT-3 are pretty good at memorizing stuff, so we must be pretty close to solving the mystery of language acquisition.)

You don’t, the thread seems to suggest, need all these complex devices like grammatical rules and syntax (grammar) trees that Chomsky and his other linguists have labored to understand.

The thing is, current AI systems that (roughly speaking) do a lot of cutting and pasting without those grammar rules and trees aren’t really all that close to understanding human language. And, worse, the thread itself, with its ideas both about what language is and how it might be learned, turns out to be a bit of a trainwreck.

Partly because the thread is largely aimed at a strawman (a caricature of what Chomsky believed in 1974, before many of the relevant strands of linguistics were developed in modern form) but mostly because it ignores two things that are crucially relevant: the complex nature of language, and what children actually do in the course of acquiring it.

The nature of language

The intuition that language might simply be memorized has some superficial plausibility - but only if you restrict your focus to simple concrete nouns like ball and bottle. A child looks at a bottle, mama says bottle, and child associates the word bottle with the concept BOTTLE. Some tiny fragment of language may be learned this way. But this simple learning by pointing-plus-naming idea, as intuitive as it is, doesn’t get you very far.

It doesn’t work all that well for abstract nouns (what do you point to when you are talking about the word justice?). It doesn’t work particularly well for sorting the fine detail of verbs [when mama points to a dog that is barking and says bark, does the word bark refer to the act of barking or the act of sitting or the act of breathing or the act of living? or to any of the other many things that might apply to the dog at that moment? Could it be an adjective, like fuzzy, or as Quine asked, refer to some undetached part of the dog?].

The naive memorization theory also doesn’t work all that well withrequests (when grandma says eat your peas, usually her grandchild is not in fact eating the peas, so you have the word eating exactly when you don’t have the action of eating).

It doesn’t give much insight into how we understand a class of words called quantifiers like some, every, and most; it’s even less clear how it would work with words like no and not (a major sore spot for current neural networks).

Meanwhile the “memorization” theory tosses off in a quick aside the place where all the real action is: putting all these bits that one might have hypothetically memorized into a meaningful whole. All the thread tells us is that all you have to is memorize stuff, and maybe add some “linking devices”:

This is true as far it goes, but too vague to actually be at all useful, the linguistic counterpart to worthless advice like “buy low, sell high.”

Moreover, it is of no surprise whatsoever to anyone working in Chomskian linguistics, because the “linking devices” is very much the grammar of rules they have been working on for decades. It’s not some revolutionary new insight or a refutation of generative grammar (which tries to understand language in terms of rules), it’s just an affirmation of what generative grammar is all about.

§

In linguistics, God is in the details. Why is the sentence John is eager to please interpreted so differently from the sentence John is easy to please? In the former, John is doing the pleasing, whereas in the later someone else is (potentially) pleasing John; ostensibly similar syntax gets interpreted in very different ways because of subtle differences in the syntax of easy versus eager; literally a whole dissertation was written about why.

Understanding such subtleties is what linguists work on. Vague talk about linking rules and memorized bits does nothing to solve any of the,.

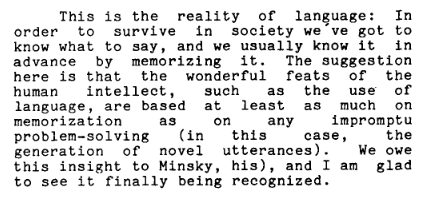

To take another example, Chapman (author the of tweetstorm) quotes at length from a 1974 essay from the linguist Joseph Becker, on the “reality of language”:

Well, ok, the passage is lyrically written (if a bit unclear) but who among us actually memorizes passages like the above, in order to understand them?

§

The real action here is not in what’s memorized (a few phrases like ‘in order to survive” , “human intellect”, “finally being recognized”, etc ) but in the linking devices that are tossed off as if (a) they were trivial and (b) of no actual interest to real linguists.

The fact that we need linking devices is precisely why we need a Chomskian “generative” theory of linguistics in the first place, one that lawfully relates syntax (eg the order of words) to semantics (the meanings of those words).. When Chapman dismisses the tree structures of linguists as irrelevant, he seems blissfully unaware of the fact that such trees have been central to the efforts at linking semantics and syntax, in key work of many generative linguists, such as Montague, Partee, Kamp, Kratzer, Grimshaw, Jackendoff, Heim, Gleitman, etc, for over a half a century.

Pinker’s 1980s work on child language acquisition, seated deeply in a Chomskian tradition, was almost entirely focused on understanding “linking rules” that connect syntax and semantics. None of this is easy (e.g., what linking rule gets you from the words in the first sentence above to a specification of its meaning? How do you even specify its meaning? What does a reader do once they have extracted the meaning?), but a simple nod to memorization just doesn’t get you far.

To read Chapman, you wouldn’t know that anybody had even tried, as if Becker invented the idea of linking rules and that nobody since seems to have considered the notion. You would also have no idea why any of that work is non-trivial.

It’d be like refuting quantum mechanics because you never personally saw a quark nor read any of the relevant literature, but you just had a really strong feeling that things couldn’t be that small.

Child language acquisition

It is an actual fact that some of what children say is memorized. But it is also an actual fact that some of it isn’t, like when a child says I breaked the window or don’t giggle me. (Note that any adult speaker could readily interpret either, despite the fact that neither is memorized

The intuition that kids just repeat what they have memorized (at the core of Chapman’s argument) has trouble with cases like I breaked the window and don’t giggle me, because it doesn’t really explain (or anticipate) the things that children say that aren’t directly attested in the input; instead, it has to leave them to mechanisms that aren’t strictly about memorization.

It also doesn’t explain how children have qualitatively mastered language by the age of three with relatively little input (far less than we might imagine GPT-4 or GPT-5 relying on).

The theory runs into even more trouble with cases like Nicaraguan Sign Language, invented and refined over the last few decades by deaf children, without a prior adult model, home sign in which children sometimes develop their own languages, and the way which child language learners transform limited pidgin languages into powerful creoles. More broadly, as Chomsky has pointed out, understanding language sheerly in terms of memorization does little to explain why human languages are the way they are, more erratic and loose than programming languages and mathematics, yet highly expressive and orderly in their own ways.

Summary

To date, nobody, ever, has given a convincing and thorough account of how human children (and human children alone) learn language. To get there, You would probably want a rich theory about how people represent meanings (which nobody has been able to develop and verify thus far), and a good theory about how those meanings are interrelated to the sentences of a language (also the subject of enormous but unfinished work).

To acquire a language is to (a) be able to go from sentences to meaning and (b) to go from intents (meanings) to sentences. All normal children manage to acquire language in this sense; no existing machine does. We don’t know how kids do it; we do know that what we are doing with machines currently isn’t really working.

Everyone in the field realizes that these are hard problems. Vague appeals to memorization aren’t new, and they aren’t real progress. (Indeed systems like GPT-3 are spectacular at memorization, but many onlookers recognize them for what they are, stochastic imitations of their input, with very little real coherence and very little comprehension. And it is worth noting that even if they did work, there would be, of course, no guarantee that they would work in a fashion that was similar to humans; AlphaGo plays a mean game of Go but that doesn’t mean it gives insight into how human players learn Go.)

Annointing a theory that isn’t really working, based purely on armchair theorizing, isn’t progress; it’s trivializing, disrespectful to the enormous work of two vast fields of cognitive science (linguistics and child language acquisition). More broadly, it’s ignoring reality. If we want to make progress, we need to start by recognizing the enormity of the problem.

Thanks to Annie Duke for nudging me to write this, and making the first draft better.

Fascinating insights!

Association seems to play a large part, seems to be so in pets as well - "ball" is simply a sound - but if used repeatedly with a round thing you pick and throw, both kids and dogs 'get' what it "means". With children, use of similarities and opposites (eg in preschool) - big dog, big tree, big house... seems useful in imparting 'bigness'. Word order, proper grammar, or even the proper word etc seem little to do with picking up language early on. Embodiment plays a vital role, to physically ground everything - up, left, heavy, hot, loud, fast, bright, tasty...

Found the idea of him being younger than the paper pretty funny, but Chapman's linkedin lists him as being at MIT in 1978. This doesn't rule out him being an extreme prodigy, admittedly