No, Virginia, AGI is not imminent

Don’t believe what you read

The most interesting thing I read yesterday was from Shane Legg, one of the founders of DeepMind, on the social media network formerly known as Twitter, arguing that Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—a term that he helped coin—was imminent.

What did he mean by AGI in this context? To his credit, he was quite clear

By AGI I mean: better than typical human performance on virtually all cognitive tasks that humans can typically do. I think we're not too far off.

I seriously doubt it. It’s also (as discussed below) not quite how he and I publicly discussed the term last year; in my view it’s a subtle redefinition that dramatically moves the goal posts. Before we get to where the goal posts were, let’s talk about where Legg wants to put them now: beating typical human performance more or less across the board.

Are we close to that?

§

At first glance, you might think so. There is no doubt, of course that machines are increasingly doing as well or close to as well as (or even better than) typical humans on a lot of benchmarks (scored exams that are standard across the industry).

But it is also well-known throughout the industry that benchmarks are often quite gameable. A nice statement of this from a few years ago from a team at what was then called Facebook is this, in a 2019 review by Nie et al of what we had learned from extant benchmarks:

A growing body of evidence shows that state-of-the-art models learn to exploit spurious statistical patterns in datasets... instead of learning meaning in the flexible and generalizable way that humans do."

Basically, beating benchmarks doesn’t tell you as much as you might think. Often when you do, it’s a statistical artifact.

The dirty little secret that pretty much everyone in the AI community knows is that doing well on a benchmark is not actually tantamount to being intelligent. This is even more true four years later, now that we have systems that ingest massive amounts of data from both public and commercial sources, quite possibly including eg sample law school and medical exams etc.

Without a sense of what it is in the training corpus, it’s almost impossible to conclude anything about what a machine truly understands and how general that is. You never know when the answer might more or less already be in the undisclosed training set. Beating a bunch of untrained humans on a bunch of tasks where the machine had a large amount of memorized data might not really tell us much.

§

Benchmarks are a lot of work to create; there often problems with them. Machines often solve them for the wrong reasons. Building them is an unsolved problem within AI.

That said, there are a lot of things for which no formal, satisfactory benchmark has been made on which I doubt machines are actually close to beating humans.

Here are a few examples I sketched in a reply to Legg.

We are not even close to machines that exceed the capacity of typical humans to cope with unusual circumstances while driving

Humans can write summaries and reliably answer many questions about original films and television programs that they watch; I doubt LLMs (or any other extant AI technology) can do this at all. (I suggested this as an informal benchmark in 2014, see little progress)

Humans can write summaries of things without hallucination; LLMs cannot do so reliably.

Humans can learn rules of games like chess from modest amounts of explicit instruction; LLMs can’t stick to explicit rules.

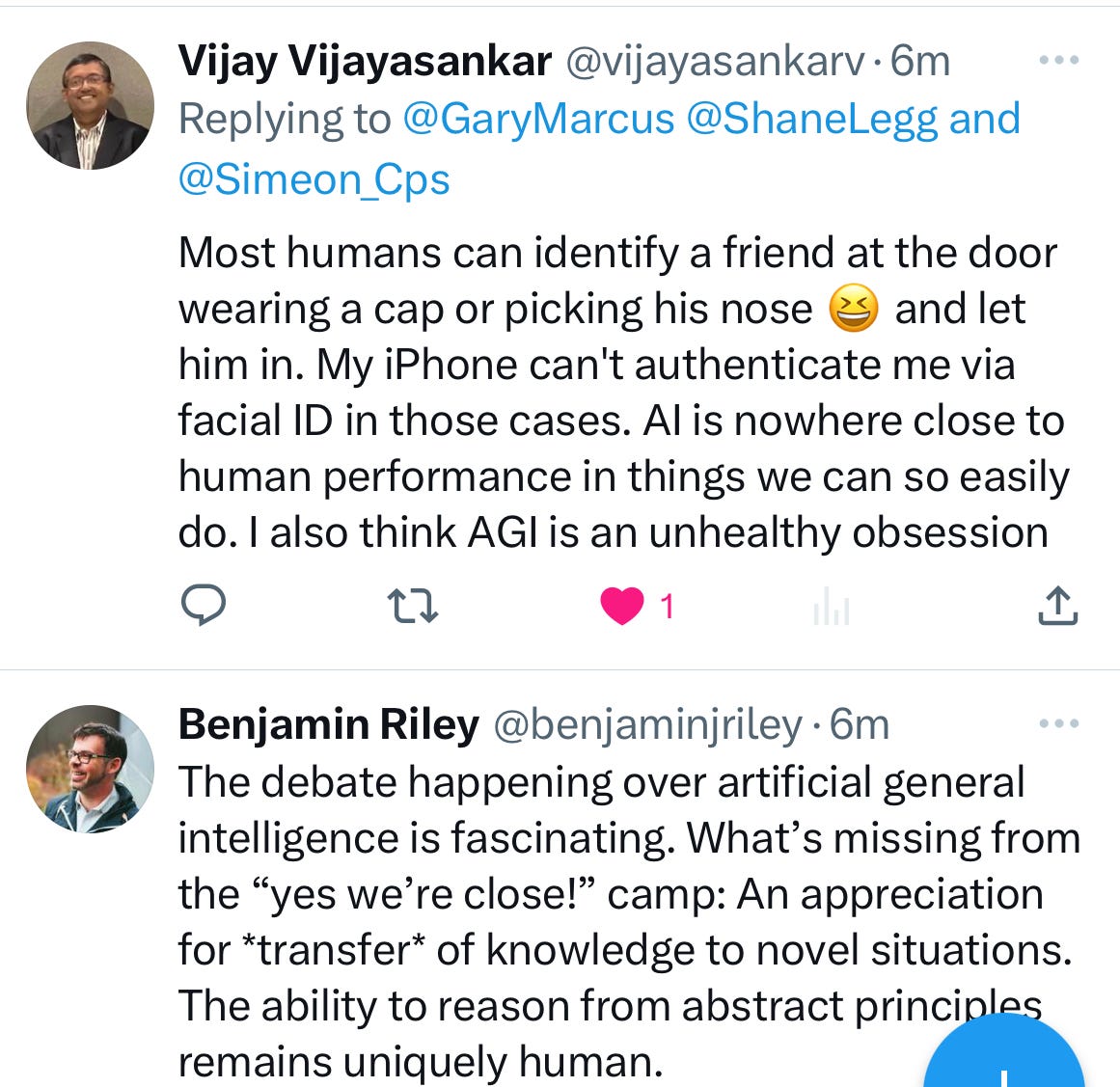

When I posted some of these on X, readers quickly pointed out other examples as well:

Needless to say, the nose-picking challenge remains unsolved. Ear-scratching hasn’t even been broached.And frankly, we still have a long way to go on all the things I always harp on: reasoning, compositionality, planning, factuality, and so on. Paraphrasing Yann LeCun, AI is still stuck on an off-ramp. Might be exciting, but it’s not yet AGI.

§

Legg’s comments that I quoted at the beginning continued in a clever way that implied that skeptics had been busy moving the goal posts:

That some people now want to set the AGI bar so high that most humans wouldn't pass it, just shows how much progress has been made!

This sounds great—but it drops the basketball rim from 10 feet to 7. Humans suck at multidigit arithmetic; that doesn’t mean I would ever buy a calculator that was merely “better than the average human” or even “better than the best human”; I expect a calculator to be right every time; that’s what it’s there for. No AGI worth its salt would brick multidigit arithmetic.

It’s a huge downgrade in our goals for artificial general intelligence to say “better than the average untrained human on many tasks”; the point is that we should expect machines to do what we ask them to do; when I press the square root button on my calculator, I expect an accurate approximation to that square root; when I press the accelerator on my car, I expect the car to go forward. If I ask a chatbot to write a biography, I expect it to summarize knowledge, not to make stuff up. An artificial general intelligence should do the things that it is asked to do, and decline to do those that it can’t, and have the wisdom to know the difference. Dropping from “as smart as the Star Trek computer” to better than Joe Sixpack should not be our goal.

§

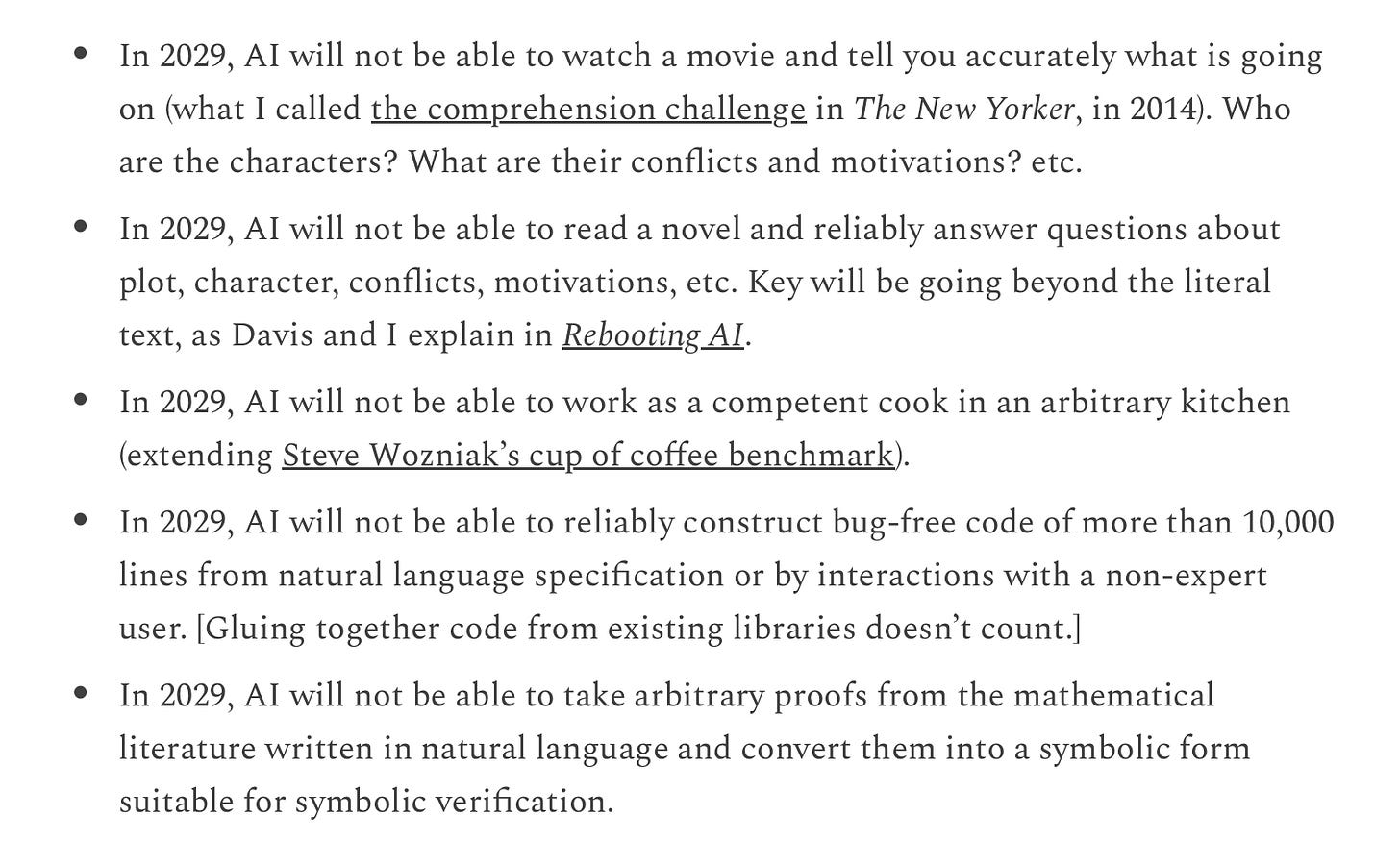

Things have actually changed, quite a bit, in a subtle way.A year and half ago, when I offered Elon Musk a bet about when AGI would come, the field generally thought my criteria were reasonable. (The Long Now foundation offer to host the bet, and Metaculus posted them on their prediction site). Three were things that ordinary untrained humans could do, but two were not. 18 months ago, before the LLM euphoria, we all took for granted that AGI wasn’t just about beating ordinary humans.

§

Legg’s 2023 standard, merely beating the ordinary schmo, is far less ambitious.

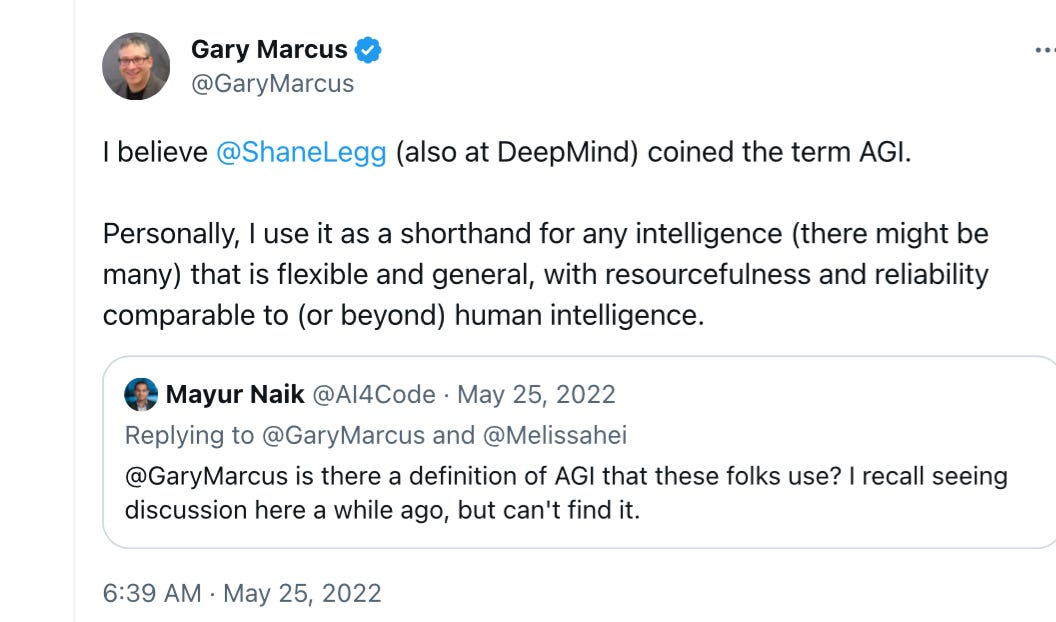

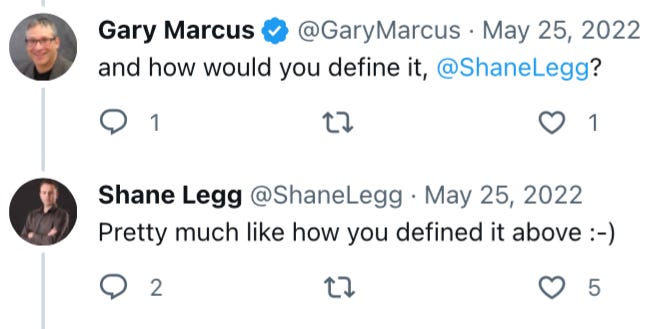

Whose goal post changed? Not mine. 18 months ago I offered a definition of my own, and asked Legg about it.

Here’s what I said

and what Legg said when asked how he would define AGI

There was no controversy back then.

In my view “flexible and general, with resourcefulness and reliability comparable to (or beyond) human intelligence“ is subtly but importantly more ambitious than “beats most (untrained) humans most of the time”.

What would make artificial general intelligence general is generality: the ability to cope with new things. And that’s precisely where current AI is still lacking.

§

Let’s not dumb down our standards, and wind up with a bunch of machines we can’t rely on, just so that big tech can prematurely declare victory, when there is plenty of work left to do.

Gary Marcus is chuffed that some of these posts were recently written up in the Financial Times. If you are enjoying these columns, feel free to subscribe, below.

We are not even on the right road to achieve AGI. See https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/ai-insight-problems-quirks-human-intelligence/ and the book that is referenced there.

Let's take a look at a slightly deeper level. It is not so much about what the models seem to get right and seem to get wrong, but the kinds of intelligence processes that are missing from the current approach to AI. General AI is not about how many problems can be solved, it is about the types of problems that are required to achieve general intelligence.

All of the current approaches to AI work by adjusting a model's parameters. Where does that model come from? Every breakthrough in AI comes from some human who figures out a new way to build a model. Intelligence needs more than adjusting parameters.

The model constrains completely the kind of "thoughts" (meant loosely), as represented by the parameters, that a model can even entertain. Anything else is "unthinkable."

There are whole classes of problems, often called insight problems, that are not even being considered here and certainly cannot be accomplished by even the current crop of GenAI models. These problems are solved when the solver comes up with a formerly unthinkable solution. Some humans are good at these problems, but computers, so far, not so much.

The right phrase for what we are now experiencing in societal discussions on AI is 'fever'.

The fever makes people convinced of things like 'AGI around the corner'. And people's existing convictions steer their logic and observations much more than the other way around. We could say that society has an AI-infection of the conviction-engine. We do not have a proper medication against this fever, just as we do not have a proper medicine against QAnon and such. Hence, your several valid observations and reasonings have little effect. Facts are pretty much useless. Logic as well.

We are talking a lot about what AI is or is not and what it might be able to do. But maybe we should be talking more about the human side and how easily human intelligence/society can get a fever like this.

I am glad that an insider like Shane Legg feeds the fever right now as my biggest fear is that the fever will break before I will give my presentation at EACBPM in London on 10 October and my presentation will be worthless as a result...