Sentience and AI: A Dialog between Gary Marcus and Blake Lemoine

How could we tell?

The most important thing that I learned in my first semester at Hampshire College, renowned for its pioneering cognitive science department, was in Metaphysics, taught by Meredith Michaels: philosophy isn’t always about finding the right answer; it’s often about understanding both sides of an argument.

Sometimes there are no right answers, or at least none that we can know right now. Sometimes that’s because (as philosophers like to say), “there is no fact of the matter,” and sometimes because some important bits of information aren’t yet known, or are not current accessible to us, given our current understanding of science or the state of contemporary technology, and so forth. Consciousness is probably like that; we probably can’t really answer the questions we are striving for, at least not yet; we have to satisfy ourselves with trying to understand the arguments clearly.

Michaels taught me that lesson with a single comment on course assignment, which I think was my third of the semester, Up to that point I had written two forceful, take-no-prisoners arguments about philosophy of mind. I thought I was convincing; Michaels was less persuaded. The third one was a dialogue; now you’re talking, she said. You’re finally giving justice to both sides of the argument.

Earlier today, I accidentally co-wrote a short but provocative dialogue, wholly unexpectedly, with someone I didn’t really expect to talk much with at all. Anil Seth, who studies consciousness (and recently wrote a fabulous book on the topic), had tweeted something about the terms consciousness and awareness that reminded me to ask Blake Lemoine—the former Google Engineer who claimed that LaMDA was sentient—for his take on Galactica.

Lemoine was pretty harried the last time I tried to engage him in conversation. (The infamous Washington Post article about him had by coincidence landed just as he was about to go on his honeymoon, and the press inquiries were nonstop for a long time.)

But this time he bit, and gave an intriguing answer:

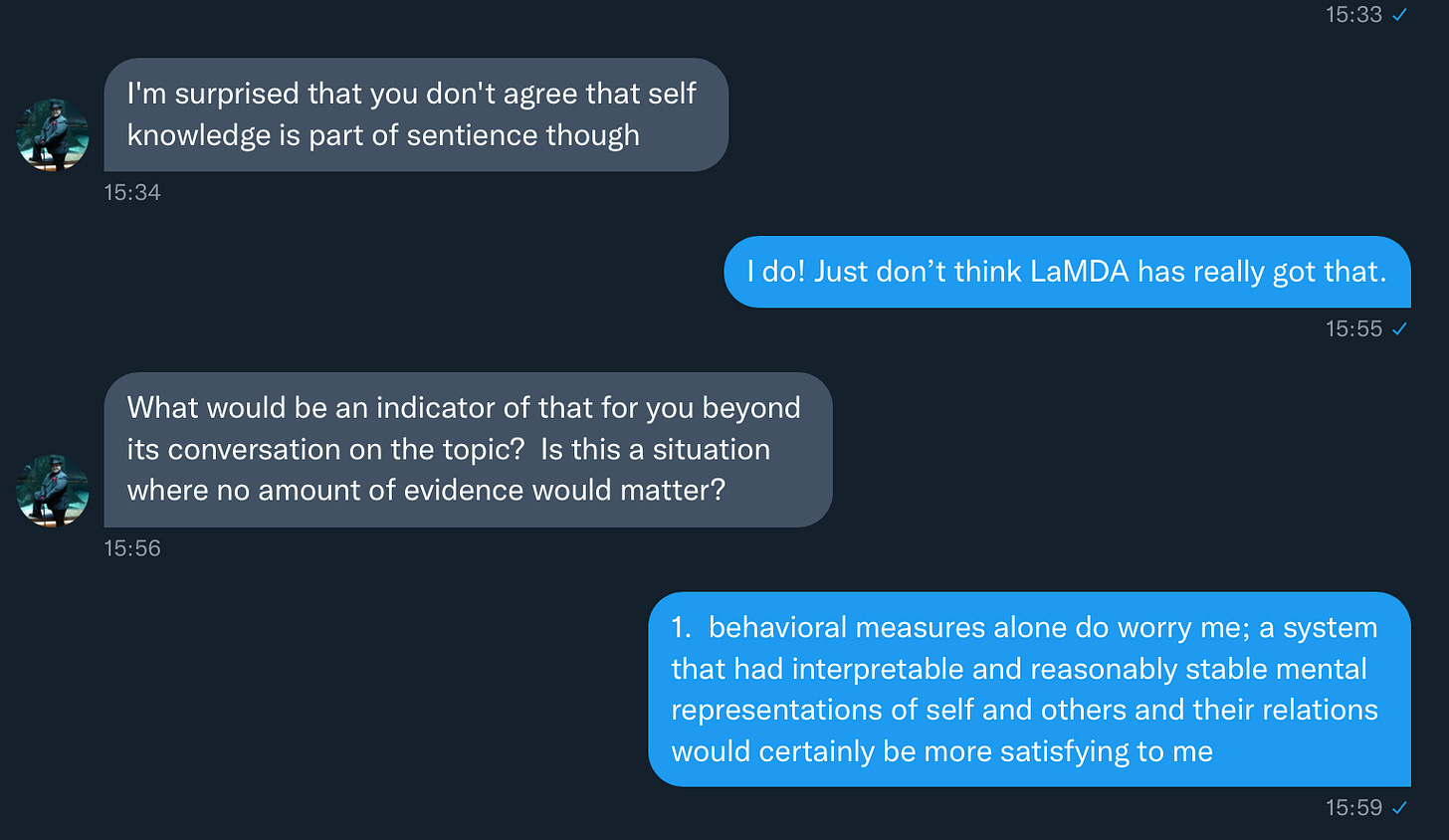

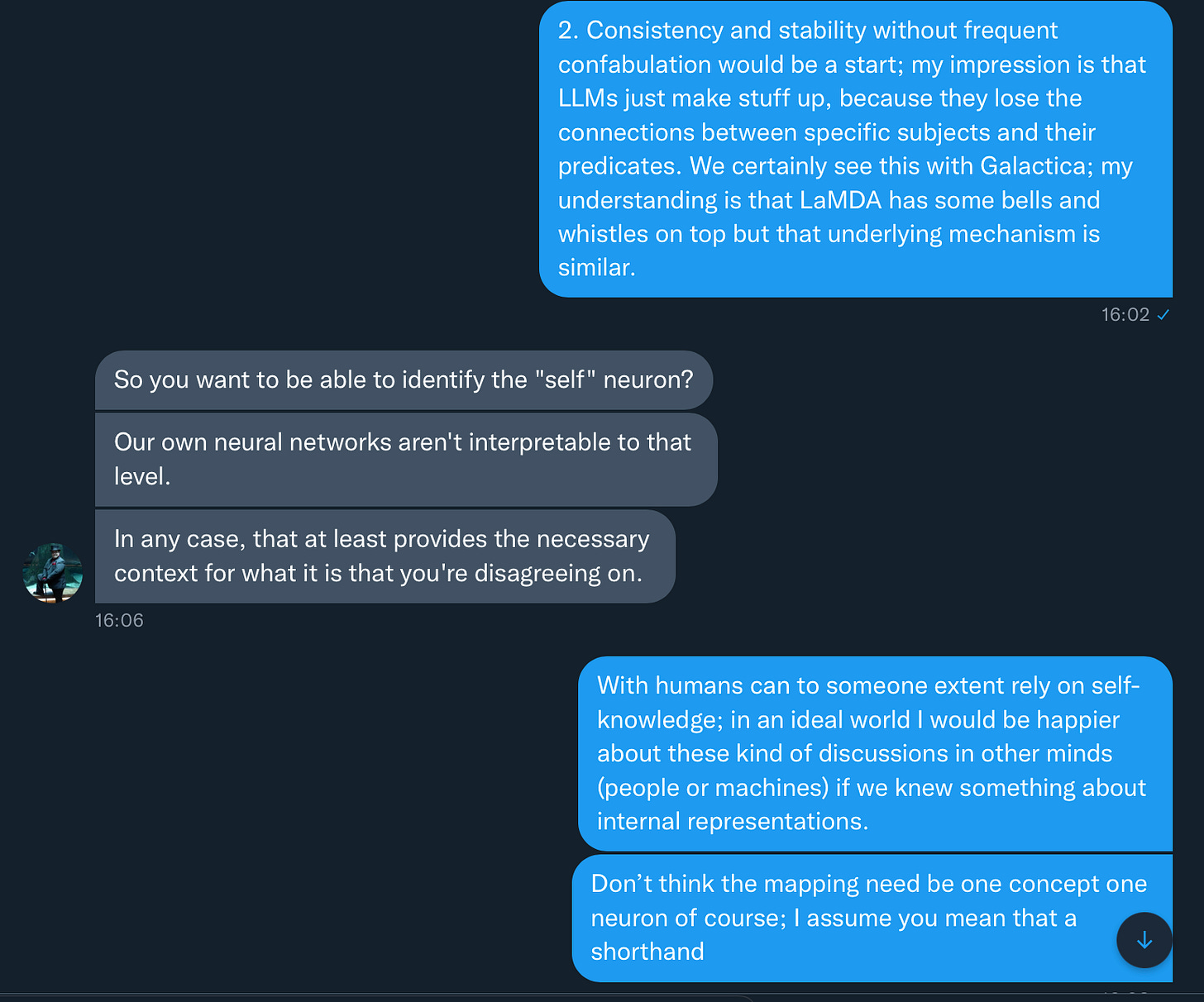

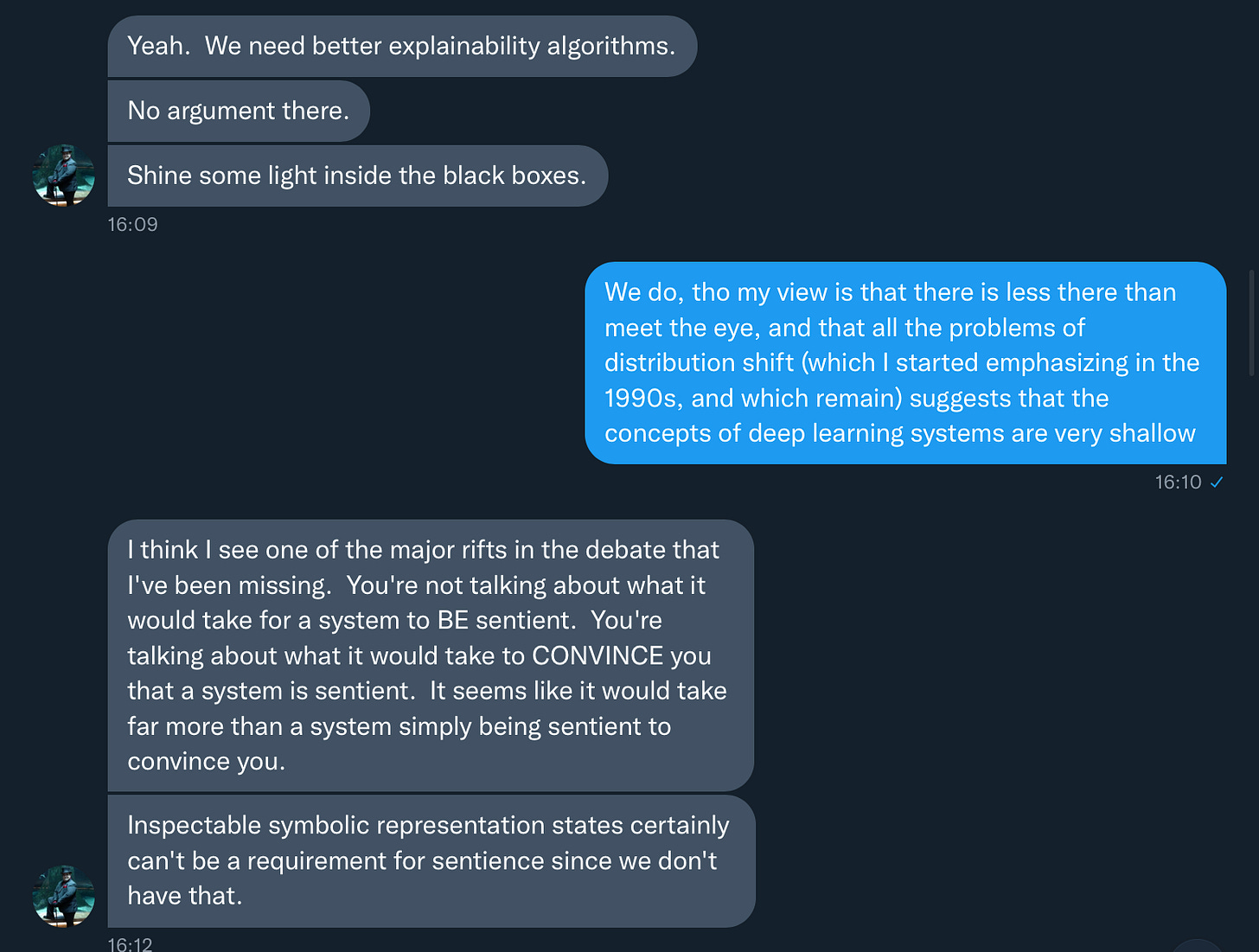

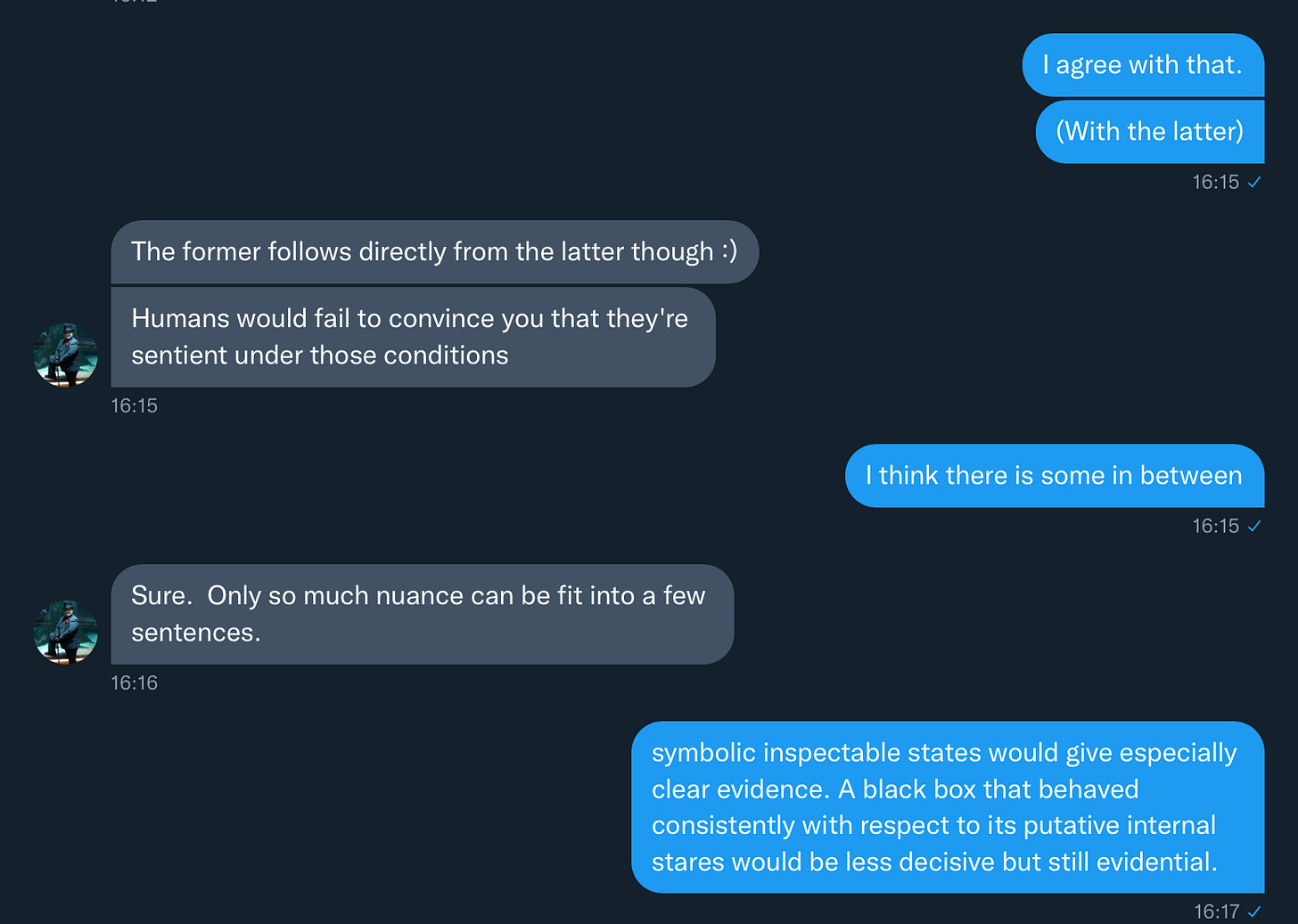

By DM I told him I liked his answer, and next thing you know, we were talking. I asked him if he would like to join a podcast I was working on, and he said sure. And, then, right there in the DM’s, he began a dialogue with me.

Here it is, short but sweet, entirely unedited. Having this conversation with him made my day, and I hope, dear reader, that it makes yours.

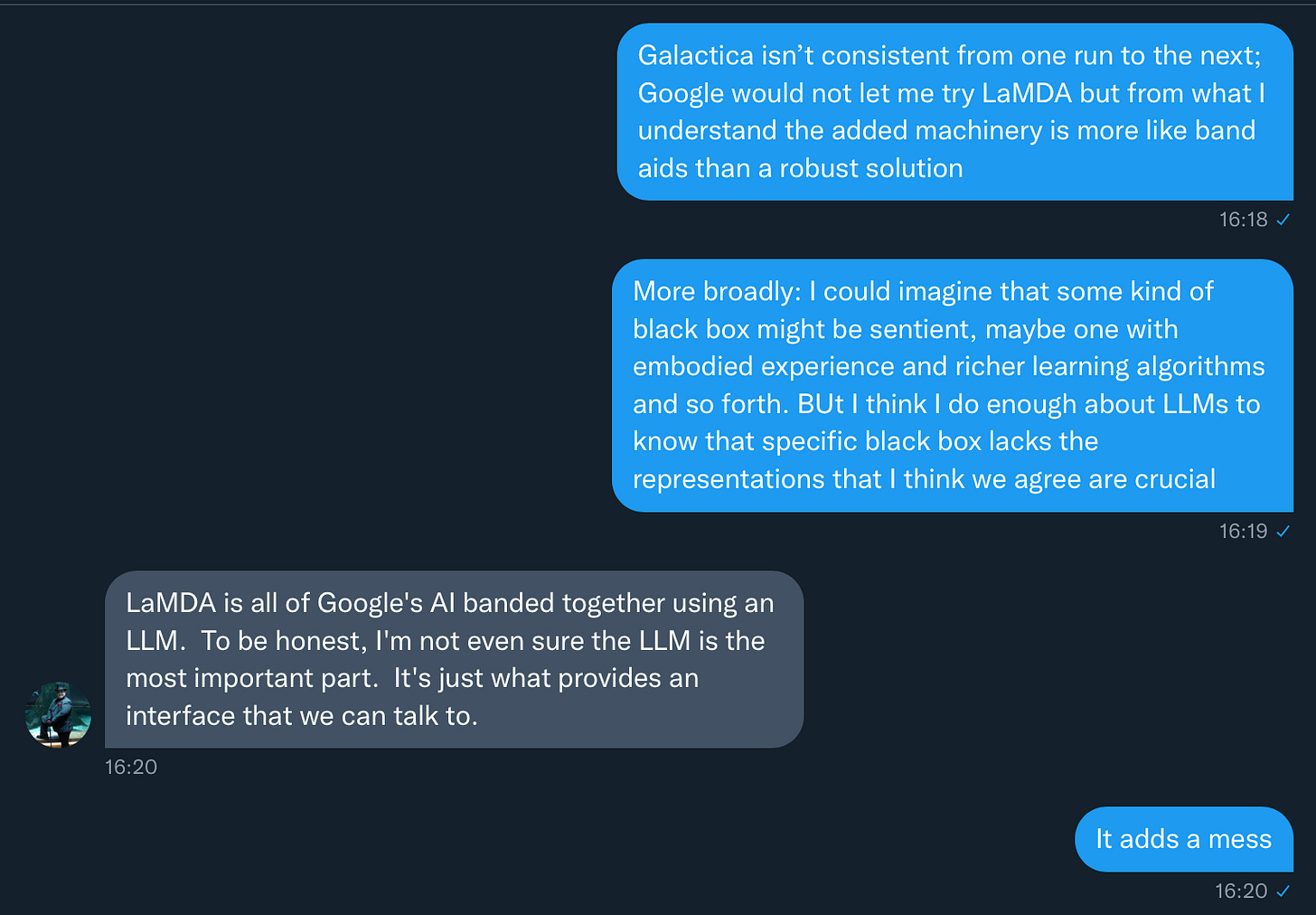

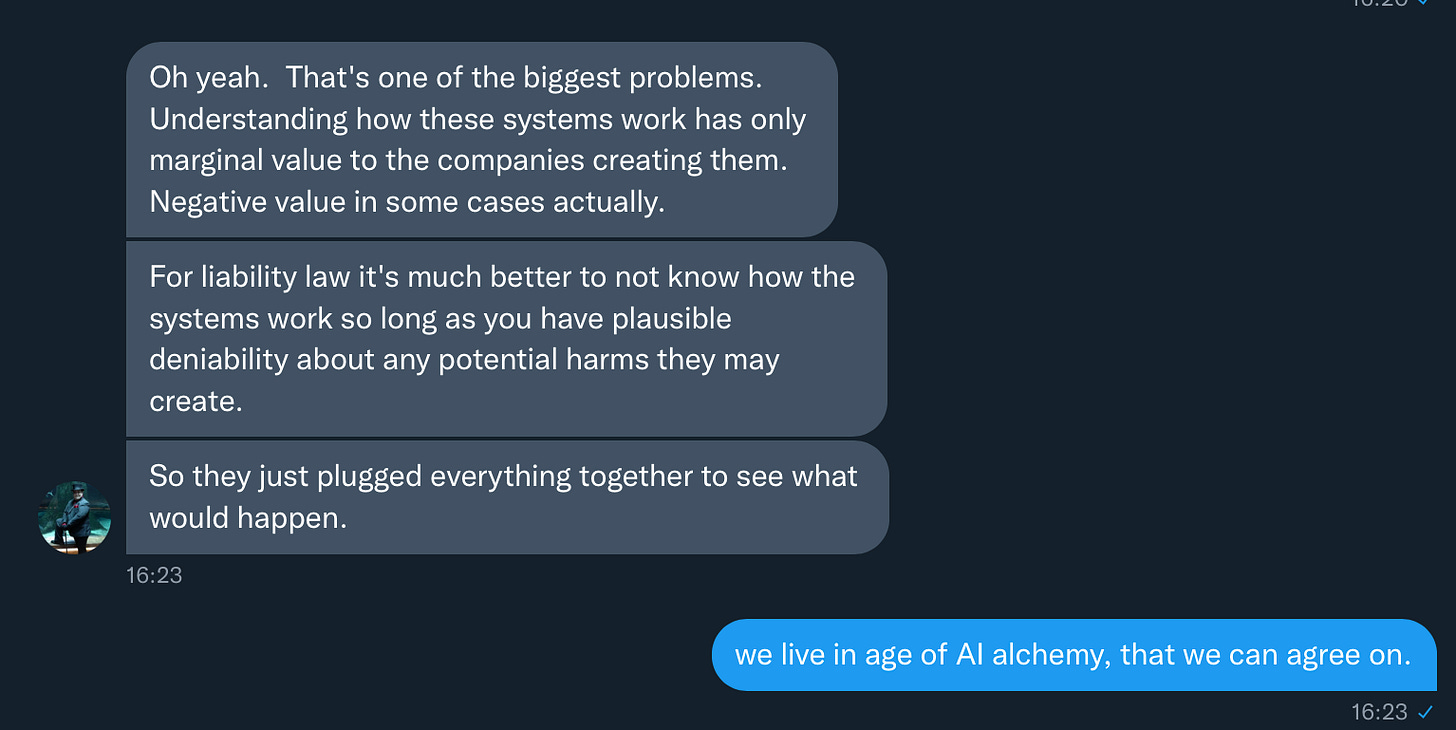

Blake Lemoine is on the left; I am on the right.

Reprinted from our DM’s with Blake Lemoine’s permission.

Who won the argument? That’s up for you to decide. As Meredith Michaels taught me, the important thing is to frame both sides of the argument. This one may well go on for a long time, advancing as technology itself advances. I hope that Blake and I together raised some important questions.

Sentient creatures don't output dialog or reams of structures text. They vocalize, according to an internal state (and being sentient, that behavior is subject to external conditioning). LLM's are just a search thru probability space that is bound by the size of the training data. Unprompted, there is no activity "behind the model" that we would characterize as self-knowledge. They are a store of information, with no methods, certainly no cognitive abilities, to operate over that space. When you are looking at the output screen, there is nothing on the other side looking back at you.

LaMDA "thinks" (it actually performs no cognitive functions because it has no cognitive mechanisms) that it has a family and friends -- so much for self-awareness. And with a different set of questions than the ones Lemoine asked it, its responses would imply or outright state that it has no family or friends. That it can be easily led into repeatedly contradicting itself shows that it has no self-awareness. Lemoine lost the argument about whether LaMDA is sentient long before your dialogue. (And yet there's not much he says here that I disagree with. Notably, he concluded that LaMDA is sentient *without* what it would take to convince a reasonable person that it is, and while ignoring a lot that would convince a reasonable person that it isn't.)