The race for "AI Supremacy" is over — at least for now.

Decades of government kowtowing to Big Tech has thus far failed to produce a decisive victory

The race for "AI Supremacy" is over, at least for now, and the U.S. didn't win. Over the last few weeks, two companies in China released three impressive papers that annihilated any pretense that the US was decisively ahead. In late December, a company called DeepSeek, apparently initially built for quantitative trading rather than LLMs, produced a nearly state-of-the-art model that required only roughly 1/50th of the training costs of previous models, — instantly putting them in the big leagues with American companies like OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic, both in terms of performance and innovation. A couple weeks later, they followed up with a competitive (though not fully adequate) alternative to OpenAI's o1, called r1. Because it is more forthcoming in its internal process than o1, many researchers are already preferring it to OpenAI's o1 (which had been introduced to much fanfare in September 2024). And then ByteDance (parent company of TikTok) dropped a third bombshell, a new model that is even cheaper. Yesterday, a Hong Kong lab added yet a fourth advance, making a passable though less powerful version of r1 with even less training data.

None of this means however that China won the AI race or even took the lead. American companies will incorporate these new results and continue to produce new results of their own.

Instead, realistically, we are quickly converging on a tie — with some style points to China, for doing so much without hundreds of thousands of Nvidia H100s.

Others may catch up, too, because LLMs just got a lot cheaper, and consequently the requirement for vast arrays of special purpose hardware has somewhat diminished. There is almost no moat left whatsoever; new technical leads very short lived, measured in months or even weeks, not years.

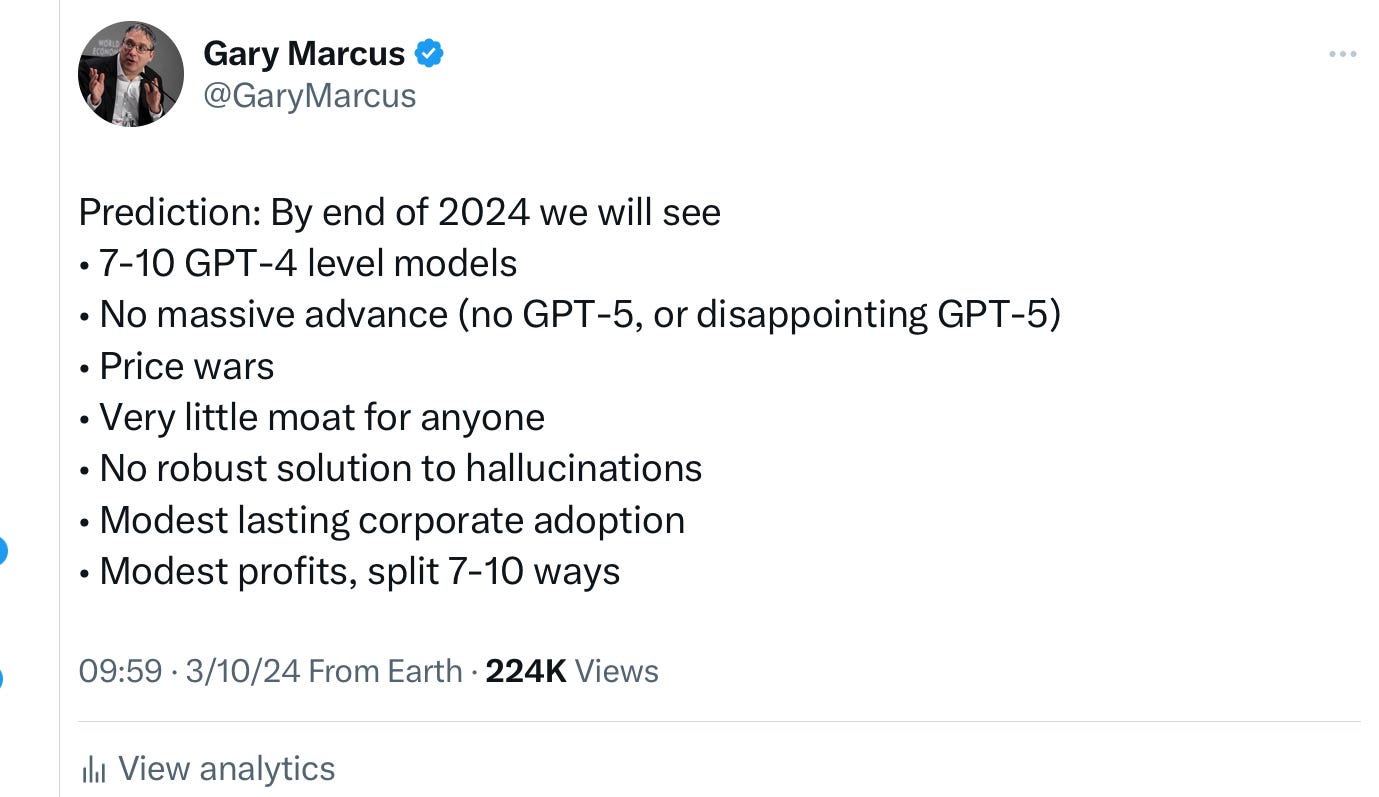

Essentially all the trends I foresaw in this tweet a year ago have just been accelerated:

And by the way, we still have no GPT-5.

§

There are many questions one might ask at this point, and some lessons learned. Here are just a few questions one might wonder about.

What does all this mean for OpenAI and the new StarGate initiative that Donald Trump announced ?

What does all this mean for Nvidia?

What does this mean for consumers?

How did China manage to catch up so quickly?

Is this race a good thing?

Is there any hope for the United States to regain a clear lead?

§

On the first question, China’s recent advances are terrible news for OpenAI. Two years ago, they were on top of the world, having just introduced ChatGPT, and struck a big deal with Microsoft. Nobody else had a model close to GPT-4 level; media coverage of OpenAI was endless; customer adoption was swift. They could charge more or less what they wanted, with the whole world curious and no other provider. Sam Altman was almost universally adored. People imagined nearly infinite revenue and enormous profits.

Fast forward to now, and what is unique (if anything) about OpenAI is far less clear.

It's no longer clear that they are state-of-the-art, and if they have a decisive technical lead, it's not obvious. Competitors have largely caught up, and in many cases undercut them on price. Customers are considering alternatives; there is no longer a sense that OpenAI is the only provider customers can turn to. OpenAI’s relationship with Microsoft has soured. Altman's credibility has diminished; his latest infrastructure play is being openly mocked (more about that in a future essay). Dozens of employees, including at least two cofounders and the CTO, have left (some for rival companies like Anthropic and others to start their own).

GPT-5 has yet to arrive, and when OpenAI introduces new models, competitors quickly catch up. There is no obvious moat whatsoever. A rumor I heard at Davos, which fits with some earlier reporting from the Wall Street Journal and another well-placed source I read recently, is that OpenAI is struggling to build GPT-5, focusing instead on the user interface in an effort to find a different, less technical advantage.

Meanwhile, revenue (order of $5B) has been modest, compared to outlays that have been much greater; no actual killer app (relative to the costs) has emerged. The economics simply no longer make sense, and at this point, DeepSeek appears more open and innovative than OpenAI.

Realizations about Deepseek are already reverberating. Altman has already cut prices twice in the last few days, and we already know from his own testimony that OpenAI has been losing money on ChatGPT Pro; as Grady Booch observed on X, “Now he’ll be losing money faster.”

I have said it before, and I will say it again—OpenAI may well become the WeWork of AI.

§

Nvidia could soon take a serious hit, too, for two reasons. First, the DeepSeek results suggest that large language models might be trained far more efficiently going forward. Nvidia has basically been getting rich selling (exceptionally well-designed) shovels in the midst of gold rush, but may suddenly face a world in which people suddenly require far fewer shovels.

Second, the DeepSeek results suggest that it is possible to get by without NVidia's top-of-the-line chips. Devices shipped in armored cars and traded on the black market might suddenly seem "nice-to-haves" rather than must-haves.

Building $500B worth of power and data centers in the service of enormous collections of those chips isn't looking so sensible, either.

§

If all this is true, the CHIPS Act, which was designed to slow China in the AI race, may turn out to be one of the worst backfires in history. (I tried to warn a number of people in the Biden administration about this possibility in the summer of 2023; instead of listening, they recently doubled down, in one of Biden's final executive orders.)

The most obvious worry was that the CHIPS Act would encourage China to build its own chips. People in the White House indeed foresaw that, and China has in fact already invested many billions towards that end. Still, many in Washington appeared to see the export controls as an urgently needed delaying tactic, perhaps guessing that it would buy the US a few critical years and somehow secure a permanent advantage.

I never bought this argument because I figured that getting to GPT-5 first might buy the winner better boilerplate text writing, but not military genius. Getting there first just wasn’t going to matter in the long run, any more than a US company to getting to GPT-4-level GenAI did, in the the grand scheme of things; as we saw this week, the advantage was fleeting.

Nonetheless, the Biden administration, perhaps caught in the hype, seemed willing to gamble an awful lot for a short-term advantage, even if it meant straining relations with Beijing or spurring China’s own future innovation in silicon manufacturing. (Trump’s boosting of Stargate seemingly fits with the same magical thinking in LLMs, premised on the same hope of achieving a supremacy that may never come).

Instead, as we have seen in recent weeks, Silicon Valley’s initial advantage in LLMs evaporated quickly, despite export controls..

But not (as some of us thought) because China ramped up H100 equivalents quickly (a big multi-year job, far from complete), but because they figured out how to work around them.

We accidentally upped their technical game. In the FT, Angela Zhang argued, "China’s achievements in efficiency are no accident. They directly respond to the escalating export restrictions imposed by the US and its allies. By limiting China’s access to advanced AI chips, the US has inadvertently spurred its innovation.”

And maybe kneecapped our greatest silicon company, Nvidia. In exchange for very little, aside from a brief stock bump for Nvidia (which prospered for a while when too many people bet wrongly that the answer to AI lay in their premium chips).

Of course, as Miles Brundage pointed out in an interview earlier this week, defending export controls, the game is hardly over, and maybe having gobs of H100s or Blackwell Chips will still matter a lot. His take, given in the quote below, is valid, and I recommend Brundage’s full interview, a terrific defense of export controls, for balance relative to mine. That said, I think he undersells software advances and oversells hardware quantity; I urge you to judge for yourself).

In his words:

Certainly there’s a lot you can do to squeeze more intelligence juice out of chips, and DeepSeek was forced through necessity to find some of those techniques maybe faster than American companies might have. But that doesn’t mean they wouldn’t benefit from having much more. That doesn’t mean they are able to immediately jump from o1 to o3 or o5 the way OpenAI was able to do, because they have a much larger fleet of chips.

I agree with Brundage that chip supply will still matter, but at the same time it is clear that the game has changed.

§

Perhaps the big winners will be consumers; to the extent that LLMs are useful (despite their reliability woes), they are about to get a lot cheaper.

Then again, cheaper might not be better. If the race to LLMs continues to be unregulated in the US, and LLMs remain detached from reality, rushed development cycles and intense global competition might well exacerbate risks of misinformation, biased outputs, privacy breaches, and misuse by malicious actors. We might all lose — and lose faster.

§

China caught up so quickly for many reasons. One that deserves Congressional investigation was Meta's decision to open source their LLMs. (The question that Congress should ask is, how pivotal was that decision in China's ability to catch up? Would we still have a lead if they hadn't done that? DeepSeek reportedly got its start in LLMs retraining Meta’s Llama model.)

Putting so many eggs in Altman’s basket, as the White House did last week and others have before, may also prove to be a mistake in hindsight. Many questions have been raised about his credibility; stars such as Sutskever, Murati, and Amodei have left, and he has offered little technical vision. Altman may be a master salesman, but Musk is correct that the US should not be so reliant on him and should not have given him such an eminent seal of approval based on so little.

In a brutal, viral tweet that captures much of my own thinking here, the reporter Ryan Grim wrote yesterday about how the US government (with the notable exception of Lina Khan) has repeatedly screwed up by placating big companies and doing too little to foster independent innovation:

§

Unless something changes, we may see years without either country taking a decisive lead, with or without a $500B investment in infrastructure.

My bet is that other things being equal, where we will be in three years is threefold:

Advances will be more incremental than before and quickly matched. GPT-5 or a similarly impressive model will come eventually, perhaps led by OpenAI, a Chinese company, or maybe a competitor like Google will get there first. Whichever way it falls out, the advantage will be short-lived.

Models will continue to get more efficient and less expensive, but hallucinations and reliability problems will persist.

Contra Silicon Valley scuttlebutt, neither country will achieve AGI by the end of 2027. Racing endlessly around LLMs will sap resources that might go into developing more original ideas.

§

The only hope for the US to regain a clear lead is for a government agency, a US company, or an academic lab to think outside the LLM box. The moves around LLMs are simply too well understood for anyone to get a decisive lead there anymore. Furthermore, as I have argued for years, LLMs are too opaque, too unwieldy, and too difficult to debug and verify. The answer lies elsewhere; betting our future on that single idea is foolish.

The race to AGI will be won not by the country with the most chips but by the one that best fosters true innovation. That could be the US, China, or perhaps some other country less locked into LLM orthodoxy, and more willing to bet big on new ideas.

Gary Marcus’s next essay will reevaluate the parallels between OpenAI and Theranos.

While these are all great numbers from the Chinese companies, and that probably means usable and affordable models for certain tasks will be possible, I am going to be careful to draw conclusions before there is more than just some *benchmark* numbers blogs and such. And *selected* benchmarks at that.

The tasks are very specific (i.e. math) and they are benchmarks. Do we know the test data wasn't part of the training data? And even if we know it wasn't *exactly*, might we be running into situations where the *variability* of the test and training data is becoming the issue?

Take DeepSeek V3 (37B parameters, right, what size?). It does 90.2% on MATH-500, but that is a number with (EM) attached, so "exact match" with the reference answer. Ouch. That is a warning sign for me. The other two math benchmarks next to it are 39.2% and 43.2%, both Pass@1. So, does it do well on math?

The vibe I am a little bit getting is the race for benchmark numbers in the 1990s (first MIPS was the big thing, then FLOPS).

And then, additionally, we all are going to use DeepSeek and other Chinese models and all our input and replies ends up in trustworthy hands, right? And we're going to trust what comes out of that when it's something other than math, right?

"Building $500B worth of power and data centers in the service of enormous collections of those chips isn't looking so sensible, either."

Exactly.

In fact, it's looking like a massive waste of money, time, and attention. In the style of absurd exaggeration and tech hubris we've come to expect.

I'm impressed with the name of the initiative. Stargate. Exactly the kind of semiliterate nonsense that I'd expect from our tech oligarchs.

Where and how were these guys educated?