AlphaGeometry2: Impressive accomplishment, but still a long path ahead

What GoogleDeepMind’s latest does and doesn’t show, and what we like about it

The headline editor at TechCrunch who wrote the headline above (we added the emoji) got a little over his skis, as headline writers so often do. DeepMind didn’t make that claim, and it isn’t true. But the new work is interesting, both for what it can do, and what it can’t do (or at least hasn’t done).

Let’s start with what DeepMind actually claimed. Their report published February 5 was “Gold-medalist Performance in Solving Olympiad Geometry with AlphaGeometry2”. Before we get to evaluating this more modest but still strong (and hint: not fully correct) claim, we have to start with a little history.

Back in July, a team at DeepMind announced that they had built an AI system that could perform at the silver-medal level — almost gold-medal level — on math problems from the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO), the world’s most prestigious and most challenging math competition for the top high school students.

As Gary discussed in a blog back then, the AI system itself consisted of two completely unrelated parts: AlphaGeometry2, for the geometry problems and AlphaProof, for all the other kinds of math problems. The team that built AlphaGeometry2 has now published a new report, giving lots of technical information about how it was built and how it works, and announcing that, when they tested this on all the 50 IMO geometry problems from 2000 to 2024, it correctly solved 42 of them — 84%. By contrast, the average IMO high school-aged human gold-medal winner solves 81.8%; the average silver-medal winner solves 67.8%; and the average bronze-medal winner solves 54.2%. (Hopefully, the team that built AlphaProof will publish a similar report soon.)

There is no question that this is a very impressive accomplishment. These problems are all tough and some of them are awfully tough. If you want to see, here is an online list of all the IMO geometry problems from 1959 to 2018.

How excited should we be, and what does it mean? Answering that is subtle, and requires a clear understanding what’s going on behind the scenes:

AlphaGeometry2 is not a generic chatbot; rather it was built quite specifically to solve IMO geometry problems. Its construction involves the combination of numerous highly specialized components. Unlike DeepMind’s AlphaZero system which learned to play multiple board games, or OpenAI’s ChatGPT, AlphaGeometry2 is nowhere close to being a single general-purpose learning architecture. It is more like Meta’s Cicero system that played Diplomacy, in that regard. (See our largely positive discussion of Cicero.)

Importantly, the success rate of 84% is achieved only if the IMO problems are manually translated from the original English statement into a specialized mathematical notation. The paper reports on an experiment to use AI technology to translate the English statement of the problems into the mathematical notation; this succeeded on 30 problems. Taking this into account, the fraction of problems where a composite AI system could solve the problem starting with its English language statement is at most 60%.

Similarly, the proofs that Alpha Geometry2 generates are in a highly-stylized, hard-to-read mathematical notation. They are not written the way a human mathematician would write them.

Most importantly: The range of problems that included in the IMO and that AlphaGeometry2 can solve is very narrow. There are many kinds of geometry problems that bright high school students can easily solve that AlphaGeometry2 cannot even express, let alone solve. We will give examples below. How much work would be needed to extend AlphaGeometry2 to a system that could solve all high-school level geometry problems is anyone's guess.

None of this puts these systems anywhere close to the level of professional human mathematicians (research problems in mathematics are mostly incomparably more difficult) but it still is well beyond what was previously possible for AI systems.

Ok, but how does it all actually work? The systems turn out to be remarkably complex, and very different in nature than the chatbot LLMs that are currently the main focus of public and corporation attention in AI.

§

To start with: AlphaGeometry 1 and 2 are flagship examples of successful neuro-symbolic AI (as is AlphaProof). The core of the reasoning system is the kind of symbolic, geometric-theorem proving system that people have been building since the late 1950s. For example, to prove the classic theorem, “The base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal”, the system expresses the assumptions, “A, B, C are points, and the lines AB and AC have equal length” and the statement to be proved “The angles ∠ABC and ∠ACB are equal” and then the systems use the kind of axioms and reasoning that one learned in high school geometry class and that go back to Euclid and even earlier to derive the conclusion from the givens.

The tricky part of constructing these kinds of proofs has to do with adding supplemental elements to the basic diagram. As you may remember, it is often necessary to add extra lines or circles or points that are not mentioned in the problem statement before the proof will go through. For decades, finding the right way to add supplemental elements that will enable the proof has been a huge obstacle for automated geometric theorem proving; no one could find a really good way to do that. The major innovation in AlphaGeometry 1 was to apply machine learning to that. They took a language model architecture — the kind of AI that powers ChatGPT and its kin — but instead of training it on text on the web, they trained it on a huge dataset of proofs that they generated automatically for the purpose. The language model learned to associate certain kinds of geometric constructions with certain kinds of proof statements, and it got very good at suggesting supplemental items to add to a problem statement that would enable the symbolic theorem prover to find the proof.

AlphaGeometry2 used the same basic idea as AlphaGeometry 1, but tuned some features and added some new components. Some of these are related to machine learning but others are highly sophisticated, manually coded, pieces of mathematical software. For example, it is often useful, in looking for a proof, to have a diagram that exhibits one particular instance of a problem — one particular isosceles triangle, in our earlier example. If the proof statement is “non-constructive” — it describes the geometric situation but doesn’t indicate how you would go about creating such a diagram — finding a satisfactory diagram can be difficult. AlphaGeometry2 includes a highly sophisticated computation algorithm specifically for building diagrams from non-constructive specifications.

As a result of all this, AlphaGeometry2 is now a complex system with multiple modules, many of which are based on GOFAI [“good old fashioned AI”, as opposed to neural networks) and on conventional mathematical software rather than on machine learning. We have always felt that greater modularity will be a necessary part of future AI, and welcome these kinds of explorations.

§

Still Alpha Geometry2 is limited to problems that can be expressed in its particular symbolic language. The paper by the DeepMind team acknowledges the fact that some — 6 out of 50, to be exact — of the problems that have appeared in the IMO since 2000 have required concepts, like three-dimensional geometry, that are not covered in the current version of the language. However, the paper entirely missed the much more important fact that a lot of very basic geometric concepts are never used in IMO problems. Consequently, many geometric problems — even very simple ones — cannot be expressed in the symbolic language of AlphaGeometry2. AlphaGeometry2 thus has no chance of solving these, for the simple reason that it cannot even express them.

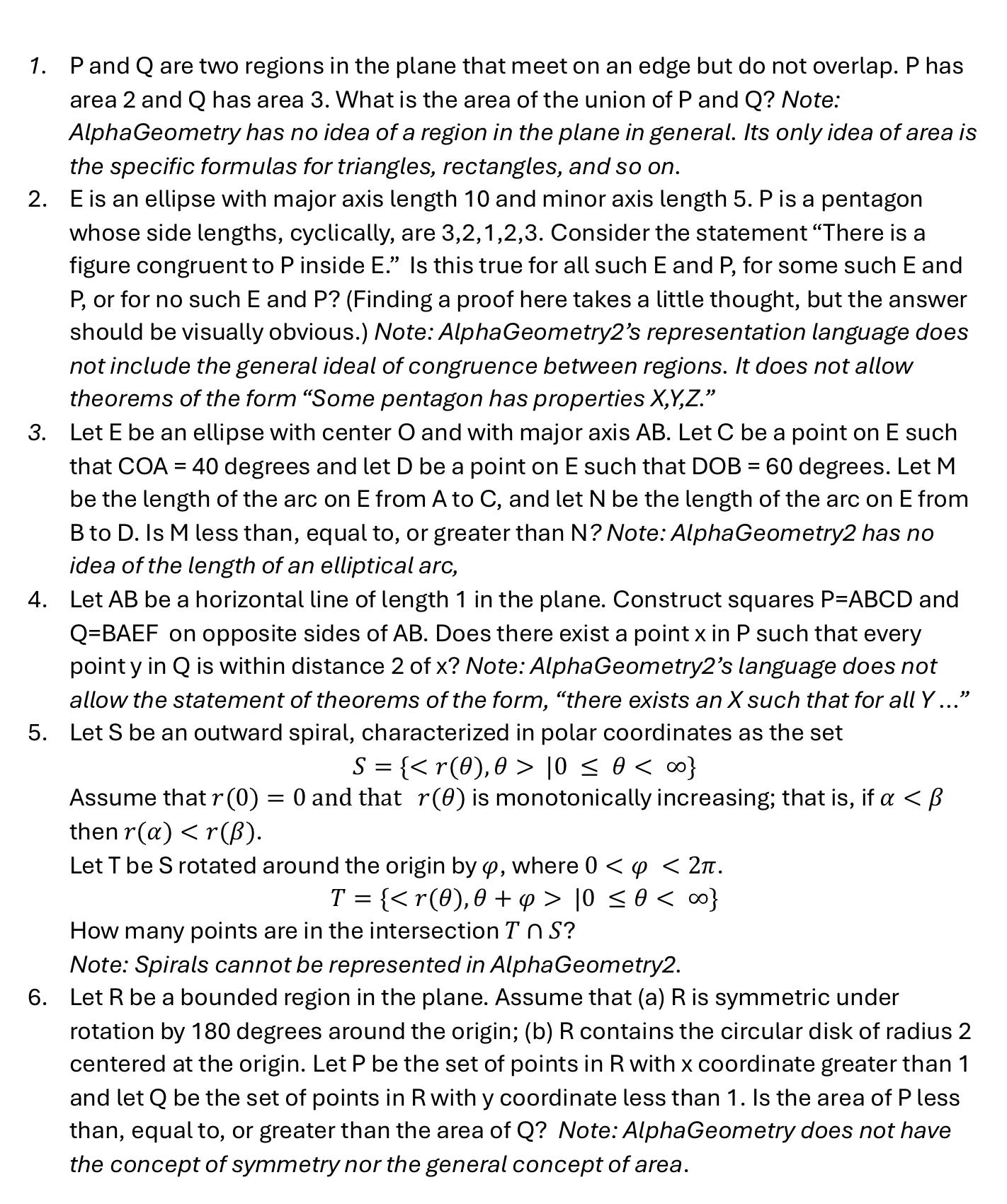

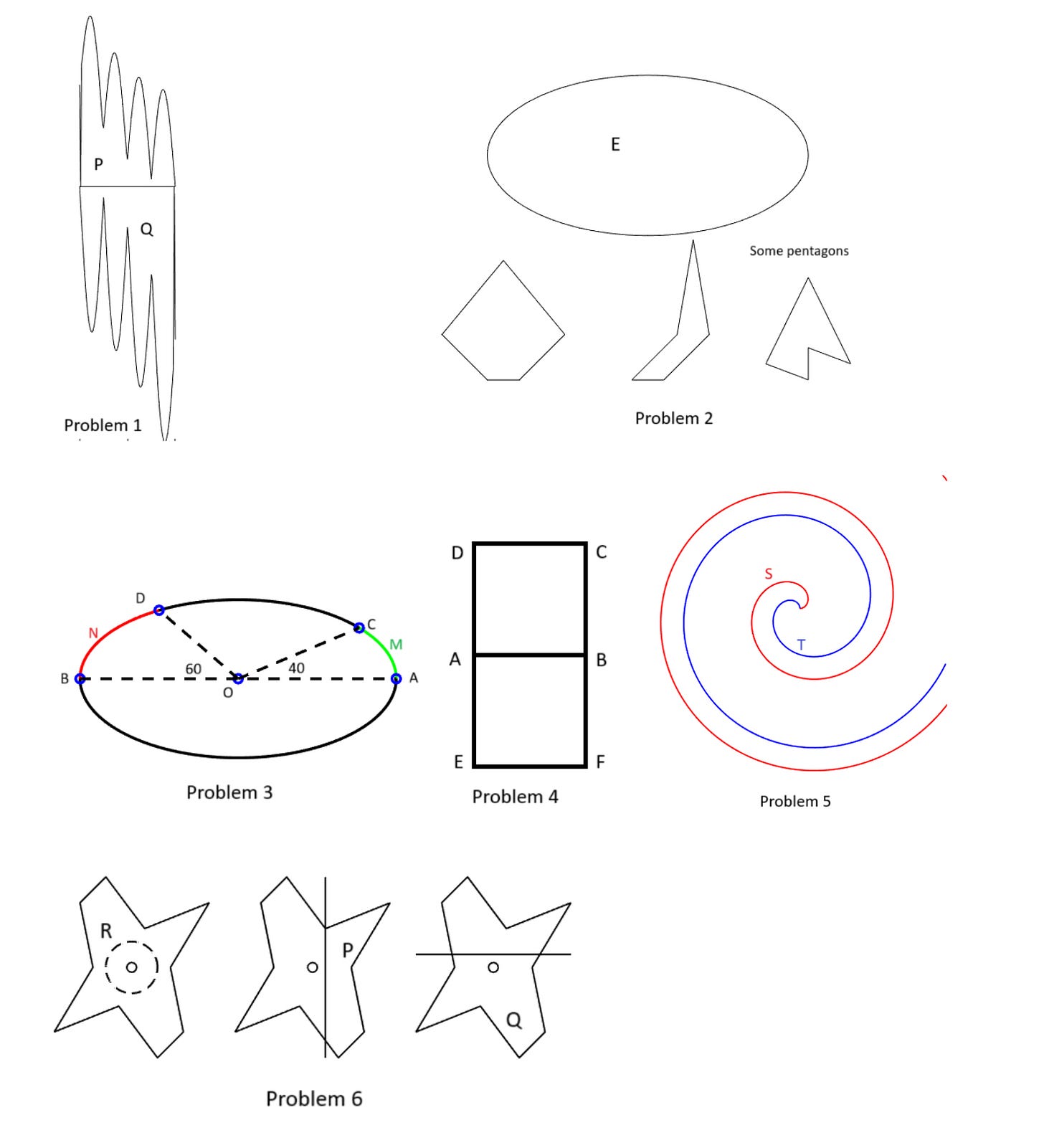

Let us give a half-dozen examples that we expect IMO-level high school students, or even strong high school math students who are not IMO stars, should easily be able to handle, but which lies outside AlphaGeometry’s current range, because of limits on the expressiveness of its language:

How much additional work would be needed to extend AlphaGeometry2 so it could handle these and the other kinds of problems that good high school students can easily solve? Is AlphaGeometry2 at all a step toward such a system, or would such a system have to be built from scratch? Frankly, we have no idea, but that additions are radical enough that we are not immediately optimistic.

None of this is to say that we think this is bad research. There is no way to know how much further the system can be extended on its current lines, but it is still very impressive as it stands.

Still, an important takeaway is a familiar one about benchmarks: they are often narrowly constructed, and one shouldn’t overgeneralize a strong result on a benchmark for a full conceptual understanding of a problem. AlphaGeometry as currently constituted does very well on the benchmark of IMO problems, and yet at the same time there is a whole world of geometry that lies outside its grasp.

We are not, by any means, claiming that no AIs can handle the six problems above. On the contrary, ChatGPT can certainly answer problem 1 correctly, and might well be able to answer some of the others. But chatbots like ChatGPT have their own, different, huge gaps in their understanding of geometry and of their ability to do geometric reasoning. Even if one were to glom together the best general AIs with AlphaGeometry2, the combination would fall far short of the geometric understanding and problem solving ability of high school math student with a talent for math.

§

So, with all that it mind, let’s go back through some of the claims that have been made for AlphaGeometry2

“[The system shows] Gold-medalist Performance in Solving Olympiad Geometry with AlphaGeometry2” (the title of the new AlphaGeometry2 report.) This seems too strong to us, because the system is actually sidestepping a critical part of IMO challenges: understanding the English statement of the problems; by preconverting each problem into formal notation, there is a sense in which DeepMind has given their system an unfair start, and not grappled with something essential. (This translation from English into formal systems gets even more complex in professional mathematics, where a lot is often left unsaid. We have an ongoing bet with Christian Szegedy of x.ai as to when that process of formalization will become truly automated.)

“Our geometry experts and IMO medalists consider many AlphaGeometry solutions to exhibit superhuman creativity” (from the same report). In discussions of AI, both the word “superhuman” and the word “creativity” should each immediately raise red flags. Aside from the fact that is not clear how many is “many” (the report lists just three candidates), this seems overstated. Although it is true that the AI system found ingenious solutions to geometric problems, some of which, apparently, no one has found before (mathematicians would tend toward other methods for solving the particular problems involved), it seems to us questionable whether you want to call this “creative” as opposed to merely novel or different. We see no reason at all to call it “superhuman”.

“This AI Just Figured Out Geometry” (title of a Nature podcast.) Simply false, in view of the many basic aspects of geometry that AlphaGeometry2 does not cover, as discussed above.

§

All in all, we are allergic to the hype but positive towards the work. It is disappointing that a top research team confused success on a prestigious competition with mastery of a foundational subject matter, and tiresome to see the media overhype things as ever. But despite all that, we are thrilled to see one of the big companies making serious efforts at considering new architectures and new assumptions.

Ernest Davis and Gary Marcus keep hoping the field will develop models with a deeper understanding of mathematics and the world.

Elementary Euclidean geometry was solved a long time ago. It is a known result of mathematical logic that such a geometry is a decidable theory: there exists an algorithm that solves any problem in the language of elementary euclidean geometry after a finite number of steps. It was found many decades ago. So, strictly speaking, that's an area of mathematics that doesn't require creativity anymore. Deepmind found an efficient algorithm, but I am not surprised at all.

And while this kind of realistic analysis is what the world needs when these math olympiad results are discussed, the world will get swamped by nonsensical hype about AGI instead. Sigh.

Google is really weird. It marries (often) very good science and engineering with (often) over the top marketing and buzz.

It's a different subject, but the same recently happened with their QM computing (https://ea.rna.nl/2024/12/31/googles-willow-quantum-computer-impressive-science-and-misleading-marketing/) and you could even notice the scientists squirm in discomfort.